Find yourself a top headteacher and you’ve found yourself an excellent school. This has been the shorthand for a large part of education policy over the last two decades. This focus has spawned new titles – remember ‘Super Heads’? – and waves of policies including more headteacher autonomy, less bureaucracy and importing leaders from industry.

And, this focus on headteachers is all to the good.

Much less analysed, however, is leadership of further education colleges. This is despite principals having to cope with very significant budget cuts (whilst schools and HE have been relatively protected), and managing much larger, more complex organisations.

It is also hard to think how the UK can address many of its underlying social and economic failures without a strong further education sector.

Take, first, the post-Brexit economic landscape. As immigration falls, we will have to rely much more on developing homegrown talent among the lower skilled. Central to improving the UK’s poor productivity is a much stronger core of technical skills (we currently languish 16th among OECD countries on technical skills). We stand little chance of addressing the huge regional economic imbalances without effective local colleges.

Second, further education must be recognised as a primary channel for social mobility. There is, here, a huge collective dishonesty in much media and political debate with its focus on access to a handful of the most celebrated universities. Better access to Oxbridge and the rest of the Russell Group for low-income youngsters matters, yet it’s a necessary but not sufficient condition of real, broad social mobility. Of the 2.2 million adult learners participating in further education in 2017/18: 16% had a learning difficulty or disability, and 22% were from an ethnic minority background.[i] Looking at those aged 16 to 18 in 2010, three in five (58%) of pupils from poorer families (most deprived quintile) attended a further education or sixth form college as opposed to four in ten (41%) among affluent pupils (in the least deprived quintile).[ii]

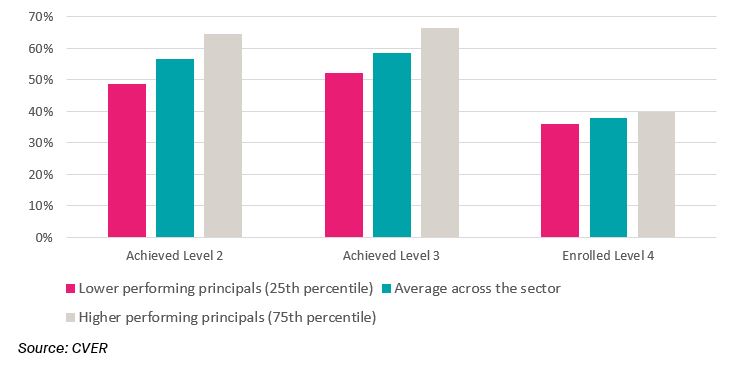

Just as headteachers matter to schools, so excellent principals matter to colleges. Analysis by academics at the London School of Economics, which followed principals over time as they led different colleges, found that leaders differ markedly in their ability to enable students to progress educationally. For instance, switching from a principal who is at the bottom 25th percentile to a principal who is in the top 75th percentile increases students’ probability to achieve a Level 2 qualification by 15.9 percentage points.

Figure 1: Likelihood of student achieving or enrolling by performance of college principal[iii]

Understanding and developing further education leadership

This is the background motivation behind an on-going SMF project on how to support and develop leadership in further education colleges.

Our initial work, to be published shortly, has focused on understanding better the delivery context for FE leaders, and developing a better evidence base on who leaders are.

Our analysis tries to put ourselves in the shoes of the FE leader – what is the world and context they inhabit and how will this evolve? Less money to start with: spending per capita has been on a steep downward trajectory during the 2000s. More competition for what funding is available: colleges must think increasingly commercially and compete for learners, such as apprenticeships, with a wide range of other providers. At the same time as feeling this commercial push, many leaders feel the pull of their social mission to offer a second chance to learners failed in other parts of the education system.

All the while, principals must navigate and adapt to a perpetually changing policy environment with some 26 major reforms this century. Not least among them, area reviews which are leading to larger colleges.

The future will bring more change and demand innovation and vision. New technologies create opportunities for virtual learning and distance learning, and for reaching new groups of learners who may have been marginalised or excluded in the past. The devolution of the Adult Education Budget will allow principals to establish their college as skills leaders in the local economy, as well as reinforcing the historic community leadership function.

Equipping current leaders with the support and skills to succeed and bring talent through the pipeline and from outside has never been more important.

This work is kindly supported by the Further Education Trust for Leadership.

[i] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/761949/FE_and_Skills_commentary_Dec_2018_final_v2.pdf

[ii] https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/bns/BN242.pdf

[iii] CVER, Effectiveness of CEOs in the Public Sector: Evidence from Further Education Institutions (2017)