This Ask the Expert talk given by Dr Maria Abreu was a textbook example of how academic expertise can illuminate complex problems of public policy.

Dr Abreu, a regional economist and a University Lecturer at the Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge, studies productivity, arguably the most fundamental challenge facing the UK economy – and thus indirectly – British politics today.

Dr Abreu, part of the ESCR’s Productivity Insights Network, reviewed the fairly dismal facts around UK productivity: British workers produce less output for every hour of work than their peers in every other comparable major economy bar Japan.

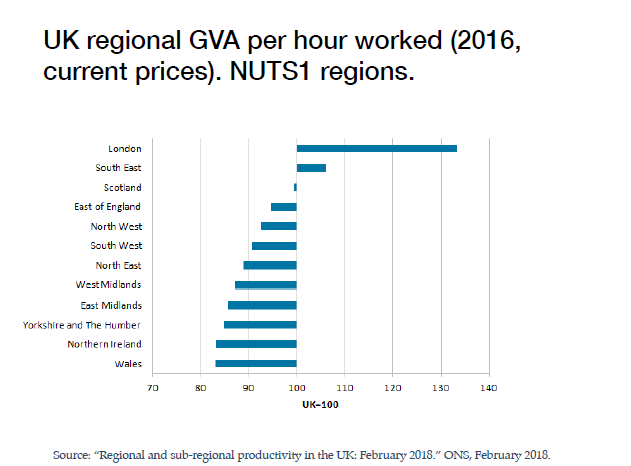

Worse, and uniquely, UK productivity is very unevenly distributed: Even our poor national average figures mask much worse performance in many UK regions outside the south-east of England, with overperformance by London dragging up the mean.

It’s not hard to see how an economy where many workers labour for relatively poor returns and where many regions outside the wealthy capital fall further and further behind that capital gives rise to political tensions and conflicts. James Kirkup, the SMF director who chaired Dr Abreu’s session, suggests that Britain’s productivity challenges are “bigger than Brexit” and may well have been a contributory factor in some voters’ decision to support leaving the EU. (https://blogs.spectator.co.uk/2017/11/lurking-in-the-budget-is-a-problem-much-bigger-and-badder-than-brexit/)

Why does the UK have such large regional disparities? Dr Abreu suggests that skills and their distribution are key here.

One issue is the way in which London’s wealth and wages draw highly-qualified Britons away from their home regions.

Although most students attend their local university, a quarter of new graduates work in London six months after graduation.

And while we have both high participation rates in HE and some of the best universities in the world, their graduates are not always using the skills they acquire at university: 30% of graduates are in jobs that don’t require a degree, a figure second only to Japan.

Meanwhile, despite the high number of Britons with degrees, many employers have deep concerns about the basic skills of the workforce: 20% of employers report hard to fill vacancies due to a lack of skills.

Here, Dr Abreu wonders if data showing workers have a lack of complex problem-solving and planning skills are actually masking a lack of basic numeracy and literacy skills.

How might policymakers begin to address these issues?

In the broadest terms, Dr Abreu suggests a need to understand the vital difference between qualifications and skills. She asks if universities should be teaching routine skills (literacy and numeracy again) as a matter of course, not as is currently the case, on a remedial and ad hoc basis. Greater emphasis on “soft skills” might also help.

In the education system, she raises questions about the value and quality of work experience, and highlights the crucial importance of good teachers in raising the aspirations of children.

Good teachers are key in raising aspirations, but difficult to attract and retain in disadvantaged areas, she notes. (This issue was addressed by the SMF’s Commission on Inequality in Education in 2017. https://www.smf.co.uk/publications/commission-inequality-education/)

Dr Abreu stresses that the whole field of productivity studies is still beset by uncertainties: even the measurement of productivity itself is contested. Some would even argue that – in the public sector at least – the concept may not even be useful at all.

One theory that she is currently pursuing relates to the nature of UK employment and contracts. Workers on short-term or insecure contracts, she suggests, may be less productive because of that insecurity: employers may be spending less on development and training for temporary, disposable workers than firms would in countries where workers are likely to remain in post for longer periods.

Such work has helped keep UK employment levels at record highs despite recent economic turbulence. Has Britain chosen, perhaps unwittingly, to have high numbers of relatively unproductive jobs as an alternative to paths taken by, say France and Italy, where workers are more productive but jobs more scarce?

Understanding – and ultimately addressing – Britain’s productivity puzzle will require more research by academics and others: The Productivity Insights Network has been formed to help lead the way here. It will also require more attention from politicians and policymakers. It’s a big, complicated issue that can’t compete for headlines and soundbites with more immediate topics like Brexit. But in the end, a more productive, balanced and fair economy might well matter more to the British population than our dealings with the EU.

This blog was written by James Kirkup, SMF Director, following our latest Ask the Expert seminar session following with Dr Maria Abreu, regional economist in the Department of Land Economy at the University of Cambridge. Ask The Expert is the SMF’s popular lunchtime seminar series, in association with the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). You can watch a video of Dr Abreu’s talk here.