The Government is set to announce that social housing tenants earning more than £30,000 (£40,000 in London) will have to pay up to the market rent.

This ‘pay to stay’ reform is expected to save the Exchequer £250m per annum by 2018-19.[1]. The money will be recouped from local authorities and used to invest in new affordable homes built by housing associations (a rather neat divide and rule on the social housing sector).

It is not clear how many tenants will be affected. The BBC has reported that it could affect 340,000 households, costing an average of £70 per week. However, this depends on how the policy is applied. The English Housing Survey shows that 484,000 households in social housing have gross incomes of over £31,200, or about one in eight of social homes [2].

Critics are right to point to risks associated with this move [3]. Perhaps the most obvious is that it may contribute to the long-term residualisation of the social housing sector. In the post-war era, the social housing sector represented a third of the UK’s housing stock now down to a fifth; and it was dominated by earners – and quite high earners at that. In 1979, 20% of households in the top decile of the income distribution lived in social housing, compared to close to zero by 2004-05 [4]. The increasing focus on the poorest in society has had detrimental consequences for the popular political perception of social housing and social tenants, has affected the mix of neighbourhoods, and, indeed, has had knock-on implications for housing supply itself. This downward spiral may worsen if higher earners flee.

But, it is also easy to overstate this argument. The theoretical advantages of social housing are threefold – subsidised rent, lower marginal deduction rates (because tenants are less likely to be in receipt of housing benefit and therefore do not have this subsidy withdrawn as they earn more) and security of tenure. Even if they have to pay up to the market rent, it is not obvious that higher earners would flee their social homes in favour of the private market, losing as they would their security of tenure and a subsidised home in the event of loss of job or income. They might also lose other advantages: the average social dwelling scores much higher on various quality metrics than the average private rented home. A much higher proportion of the former meet the ‘Decent Homes’ standard and average energy efficiency is also much higher [5]. From the opposite point of view, there may be advantages if tenants do move – with evidence showing low mobility amongst social tenants. The latter is a symptom at least in part of tenants’ risk aversion about losing the benefits associated with social housing if they were to move house. Reducing the losses to which a tenant is exposed may mean that more are ready to move to take up better-paid work.

In overplaying the argument against the government’s new policy, we may also miss important subtleties that will matter a great deal.

- The starting threshold for this co-payment must be set at the right point. Too high (George Osborne might worry) and the revenue will be modest; but too low and work incentives for tenants will be damaged severely. The sweet spot is likely to be somewhere between the point where most households lose entitlement to tax credits (£32,900 for a household with two children) and the higher rate tax threshold. In this interval, the co-payment will be levied on those exposed to only modest marginal deduction rates from basic rate tax and NI contributions. On this analysis, the Treasury may be getting it about right by setting the threshold at £30,000.

- The co-payment of rent must be tapered in – rather than tenants experiencing a sudden jump in their payments – so as to flatten any significant humps in the work incentives. Given the overall thrust of Universal Credit is to simplify and improve work incentives, any other policy is irrational.

- The co-payment must relate to equivalised resources. In adopting co-payments for higher income tenants, the Government is applying the principle of means-testing (that applies to Local Housing Allowance for private tenants) to social housing. In doing so, the Government must ensure that it is assessing not just the income of the household but also the needs of the household which will vary depending on the composition of the family and the number of children. Successive reforms have failed to follow this rather basic logic: Child Benefit was withdrawn on the basis of the highest earner in a household rather than household income; the Benefit Cap (shortly to be £20,000) takes no account of family size. Furthermore, the ‘sweet spot’ in terms of Marginal Deduction Rates varies for different sized households, meaning that the threshold for co-payment should vary as the number of children increases.

- The reform also raises more objective questions about ‘market rents’ in social housing. The sector is highly regulated and access restricted; as such, it is not part of the mainstream market. For instance, a true ‘market rent’ for a social housing property should be higher than that of an identical private dwelling because of the comparatively generous security of tenure that residents enjoy (as well as potentially other advantages described above). As such, the ‘value’ of social housing is reflective not only of the stock but of the regulation that confers additional rights on its tenants. It doesn’t appear that the Government wishes successful social tenants to pay for this advantage – otherwise they probably would all leave.

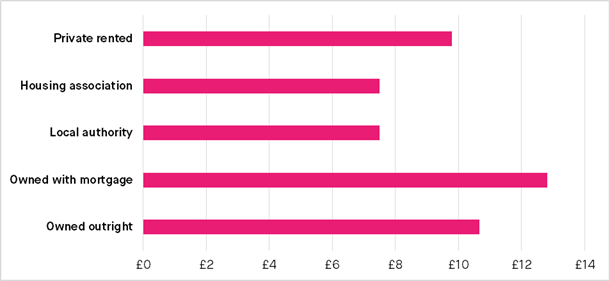

- Finally, we are in danger of diverting attention away from the major problem in social housing, namely high levels of unemployment and economic inactivity, and low pay for those that do work. Average pay for social housing tenants is much lower than for those in other tenures (see Figure below). Almost half of all employees in social housing are on low pay compared to nearer a fifth for the rest of the population. Even taking an individual with similar characteristics, social housing hourly wages are way below other sectors. Arguably, therefore, the much larger problem is how to increase the earnings and productivity of social tenants.

Figure 1: Median gross hourly pay of employees by tenure (England)

Source: SMF analysis of Quarterly Labour Force Survey, January to March 2014

—

[1] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-33399650

[2] English Housing Survey, 2012-13, Chapter 4 – EHS Households report, 2012-13: tables, figures and annex tables, Table A4.2

[3] http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jul/05/tories-social-tenant-council-housing

[4] SMF, Politics of Housing, 2013

[5] English Housing Survey 2013-14, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/406740/English_Housing_Survey_Headline_Report_2013-14.pdf