Having spent almost 20 years of my career at Westminster among politicians, journalists and officials, I’m struck by how political conversation is so utterly dominated by people who did A-levels and then went to university.

The “other people” who don’t follow that path through life really are poorly represented in the places and institutions that are supposed to represent the nation as a whole.

Even after the rapid expansion of HE entry, only half of school-leavers go to university. And for all the August excitement over A-level results day, only half of 18-year-olds do A-levels.

Yet who speaks for those people, who reflects their experience and outlook? Politics is increasingly dominated by graduates.

At the 1979 election, 68% of Conservative MPs elected were university graduates. By 2017, that had risen to 83%. For Labour MPs, the figures were 59% rising to 84%. [i]

And for all the attention given the A-level day, there are other routes to university.

The 250,000 kids who got BTEC national results this month don’t get much attention in the media, but those results matter a lot.

For a fair new of them, those BTECs are a path to university. As Kathryn Petrie and Nicole Gicheva have shown, many children from disadvantaged or marginalised groups use BTECs to enter HE. [ii]

In the north-east of England and Yorkshire, 48 percent of those white working-class children who go on to university have at least one BTEC. In the north-east, 35 percent of white working-class students went to university solely on the basis of their BTECs.

Across England as a whole, 44 percent of white working-class children who make it to university have at least one BTEC.

BTECs are also vital for black British children progressing to higher education. 48 percent of black British students accepted to university have at least one BTEC qualification, and 37 per cent go to university with only BTEC qualifications.

In short, BTECs and vocational qualification matter, a lot. Because one of the big, under-written stories of our recent economy is how whether you go to universirty makes a big difference, both economically and politically.

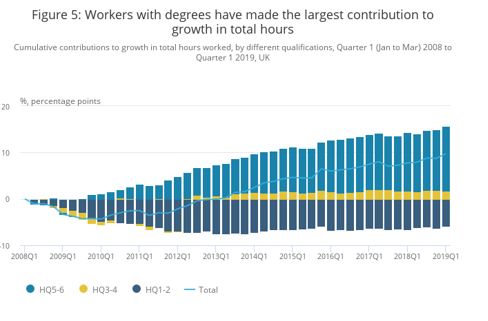

The UK economy is increasingly favouring the 14 million working-age adults with degrees over the 20 million who didn’t go to university. Some fascinating analysis from the ONS recently highlighted the changes underway in the labour market. The key fact: during the downturn after the 2007 financial crisis, workers with lower qualifications saw the largest reduction in hours.

Source: Office for National Statistics [iii]

Can the economic experience of non-graduates be entirely unrelated to their politics? Analysis of the 2016 referendum vote shows that education was a key dividing line on EU membership. Roughly 70% of non-graduates voted to Leave, while around 70% of graduates wanted to Remain.

Bridging the political divides that have followed the referendum will surely require engaging with the important role education plays in this story, and maybe delivering economic and education policies that work better for those people who you didn’t hear about on A-level day.

[i] https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/CBP-7483#fullreport

[ii] https://www.smf.co.uk/half-white-working-class-black-british-students-england-get-university-vocational-qualifications-btecs/

[iii] https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/economicoutputandproductivity/productivitymeasures/articles/analysisofcompositionalchangesinhoursworkedintheuk/2019-08-07#workers-with-degrees-made-the-only-positive-contribution-to-growth-in-total-hours-worked-during-the-downturn-and-have-been-the-largest-contributors-to-growth-in-total-hours-worked-since-then