Alcohol duty must be among the most incoherent and badly-designed parts of the UK tax regime.

Alcohol duty must be among the most incoherent and badly-designed parts of the UK tax regime. Political meddling in the face of various interest groups – the West Country cider producers, the Scotch whisky industry and the brewers – has led to vast differences in how alcohol products are taxed, and how these taxes have changed over time.

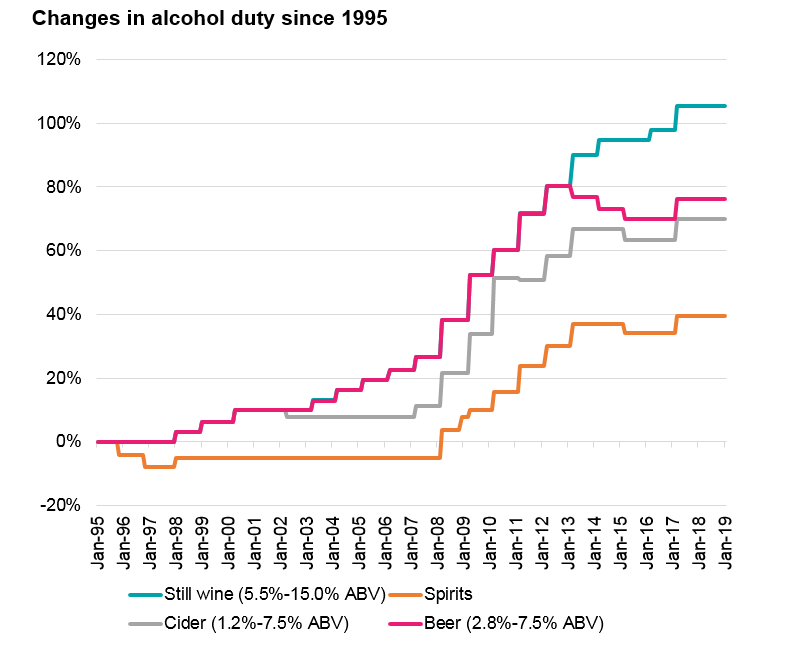

While beer duty has increased by over 76% since 1995, cider duty has increased by a smaller 70% and spirits duty by just 40% after years of freezes under the Scottish Chancellor Gordon Brown (though unlike his predecessor Ken Clarke, he did not indulge in a dram himself while delivering his Budgets.)

Wine duty has more than doubled since 1995 (graph below illustrates). With the fledgling British wine industry lacking the political clout of other drinks manufacturers, it has failed to secure concessions and has borne (proportionately) more of the brunt of alcohol duty hikes in recent years.

When it comes to raising revenue for the exchequer, curbing problem drinking, or protecting jobs in the UK, this highly distorted alcohol duty regime is far from optimal.

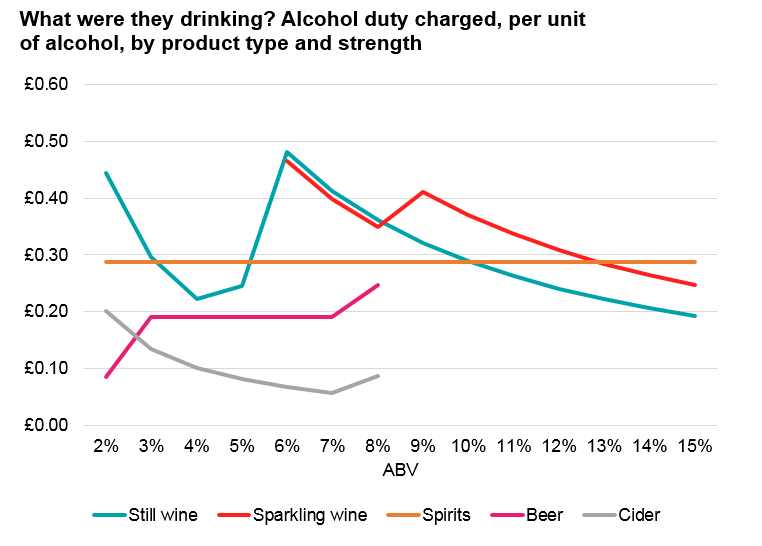

Take the graph below, which looks at the amount of duty charged on beverages, on a per-unit of alcohol basis. While a very weak 6% ABV bottle of wine faces duty of 48 pence per unit of alcohol, a 6% ABV cider faces duty of just 7 pence per unit of alcohol. While beer duty increases or holds steady, on a per-unit basis, with the strength of the product, this is not true for cider (except for the very strongest varieties) – limiting incentives to produce weaker varieties. Wine duty is even less coherent, as the graph shows.

If we want to encourage people to drink lower strength alcohol products, then surely a key principle of the duty regime should be to have one where duty rates increase with strength? Or at least one where duty rates do not decrease as product strength increases (as with wine and cider at present).

Some have defended our incoherent duty regime on the grounds of the need to protect jobs in the UK economy. But these often do not stand up to scrutiny. About 90% of Scotch whisky is exported, according to the Scotch Whisky Association, meaning changes to spirits duty have a relatively limited impact on jobs. And, despite the generous tax treatment of cider, far more are employed in British beer production (16,000 compared with less than 2,000 employed in cider production in 2017).

Alcohol duty is a great example of some of the bad things that can happen when politics and special interests – rather than evidence and common sense – shape policy. There is scope to create a much more coherent, equitable and effective duty regime in the UK.

If you would like to discuss this, please contact Scott Corfe, Chief Economist.

Email: scott@smf.co.uk | Tel: 07801 961729