In our latest ESRC-sponsored Ask the Expert seminar, Dr Simonetta Longhi, Associate Professor at the Department of Economics at the University of Reading and Research Fellow at the Institute for the Study of Labour (IZA), presented a brief overview of ethnicity pay gaps in the UK and discussed a number of possible explanations for the observed differences.

In the UK, ethnic minorities are paid less than White British people, on average. Similar findings are prevalent across most developed countries.

Brief overview of ethnicity pay gaps in the UK

Pay gaps are the difference in average (mean) pay across two groups. In the context of ethnicity, the pay levels of workers from different ethnic minorities are compared to the pay of White British workers.

Dr Longhi’s research explores the scale to which different ethnic minority groups, both immigrant and British-born, perform worse in the labour market in terms of pay than the White British working population.

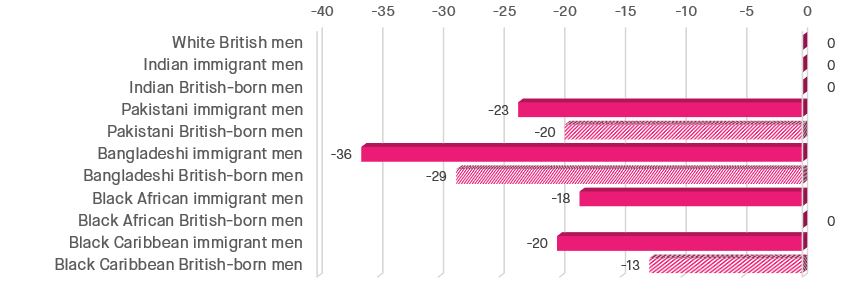

In the period 2013 – 2016, an ethnicity pay gap was not evident among Indian men (both immigrant and British-born) and Black African British-born men: on average, these groups were the only ones to be paid a similar amount to White British men.

Figure 1 illustrates that, overall, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black Caribbean and Black African (immigrant only) men are paid between 13%-36% less than White British men, with ethnicity pay gaps being of a larger scale among immigrant workers in each sub-population.

Figure 1: Ethnicity pay gaps (men)

Dr Longhi noted that ethnicity pay gaps are more prevalent across the male population. Whilst, on average, women are paid less than men, women from ethnic minorities tend not to suffer from large discrepancies in pay, compared to White British women.

Possible causes of ethnic pay gaps include, but are not limited to:

- Education and qualification levels, which tend to be lower among the Black African and the Black Caribbean population;

- Geographical location, with London possibly concealing the extent of gaps in pay;

- Occupation level, with ethnic minorities being less likely to be in higher pay managerial positions than White British workers, even if education levels are higher among some for ethnic minority workers;

- Discrimination.

Implications for ethnicity pay gap reporting

The Government recently concluded a consultation on whether large companies should be required to report their ethnicity pay gap. Details about how this reporting will be undertaken, and the nature of the underlying data are still to be announced.

Dr Longhi argued that employer reporting would yield interesting results as it would help shed some light on whether the observed gaps in ethnicity pay are firm-specific, or whether they reflect a wider occupational segregation across the economy. However, an overall reporting that involves dividing the workforce into White and non-White would risk not highlight the differentiation in pay between the minority groups. Ideally, Dr Longhi recommends that reporting be nuanced to account for different ethnicities.

The lessons from compulsory disclosure of gender pay discrepancies should be taken into consideration when devising the criteria for ethnicity pay gap reports. Whilst the ultimate purpose of pay reporting is to understand what is going on in the workplace, it is not always useful to compare employers with one another or to compare year-on-year changes. Additionally, a discussion should be held on whether it is appropriate to report mean gaps in pay or whether it would be more useful to use the median.

The ultimate aim of ethnicity pay gap reporting should be to make employers reflect on why discrepancies in pay exist within their staff and prompt them to act on reducing these gaps. It is rightly expected for such action to take a long time to devise, implement, and take effect. In the meantime, the most useful outcome would be the resulting narrative discussion of what is happening in the workplace and what can be done to reduce pay gaps on a larger scale.