Let’s reform alcohol tax to save lives

Britain’s relationship with booze is a complicated one. While politicians love to conjure up images of rural pubs, remote Highland distilleries and cider producers surrounded by bucolic orchards, alcohol of course has its darker side.

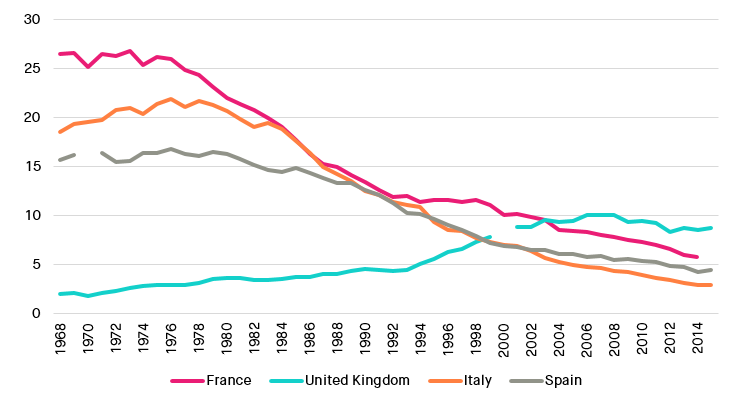

Even though per capita consumption of alcohol has declined since 2004, the UK has a higher rate of liver disease deaths than France, Spain or Italy. In the 1970s, we had a substantially lower rate of deaths than these countries.

Chart 1: Age-standardised liver disease and cirrhosis death rates, per 100,000, aged 0-64, 1968-2015

Source: WHO European HPA Database

Beyond bad health, excessive drinking contributes to a range of other social ills, including homelessness, family breakdown and crime. In England and Wales, 12% of theft offences, 21% of criminal damage and 22% of hate crimes are alcohol-related. This rises to 36% for sexual assault cases. Offenders are believed to be under the influence of alcohol in 39% of all violent incidents.

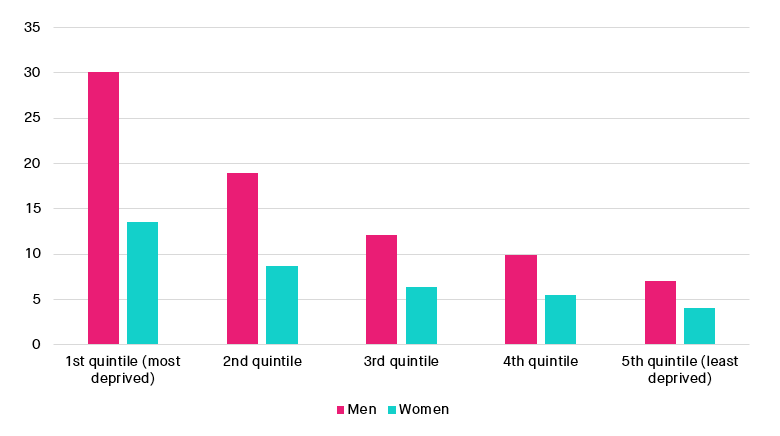

The harms associated with heavy drinking are felt unevenly across society, with those on the lowest incomes most affected. A man living in the most deprived parts of the UK is more than four times as likely to die from alcohol-related causes as a man in the least deprived parts of the country. For women, alcohol death rates are over three times higher in the most deprived areas. The North East and North West have the highest rates of alcohol-related deaths in England, followed by Yorkshire & the Humber – contributing to a sizeable life expectancy gap compared with the South of England.

Chart 2: Age-standardised alcohol-specific death rates, per 100,000, by deprivation quintile, 2017

Source: ONS

For too long, rather than tackling these problems in earnest and examining the evidence on the costs of heavy drinking, politicians have turned a blind eye, more interested in winning votes and appealing to special interest groups – including the drinks industry itself. The need to protect the Scotch whisky industry and South West cider producers has often been used to justify cuts and freezes in alcohol duty for spirits and cider. This is despite the fact that vodka, not whisky, is the most widely consumed spirit in the UK. And it is despite the fact that cheap, high strength cider is often seen in the hands of homeless alcoholics across the country. Politicians have bought into the idyllic myths, rather than the realities, of these drinks.

That needs to change, which is why the Social Market Foundation has this month called for a radical overhaul of how we tax alcohol in the UK. Done right, we can reform alcohol duty to remove “worst offender” products from supermarket shelves, and ensure that tax is focused on heavy, high-risk drinkers rather than responsible, low-risk drinkers.

What does this entail? Our report argues for the introduction of an “alcohol duty strength escalator” which levies a higher rate of tax on strong drinks. The evidence is clear; heavy drinkers tend to consume stronger products, such as spirits and high-strength beers and ciders. Increasing the tax on these products would not only discourage their consumption but would encourage drinks manufacturers to reduce the strength of the products in the first place. We know that manufacturers respond to tax incentives to make drinks healthier. For example, Carlsberg reduced the alcohol content of its low-strength lager, Skol, from 3% to 2.8%, in response to the introduction of a new duty band for low-strength beers. AB InBev has also reduced the strength of more mainstream brands of beer – including Stella Artois, Budweiser and Becks – as a means of reducing costs associated with alcohol duty. Let’s do more to nudge producers to take super-strength products off the shelves and encourage the consumption of lower risk products.

Our research also argues for the introduction of a new “Pub Relief” which would allow pubs, bars and restaurants to claim back some of the alcohol duty costs that they face. This would ensure that alcohol taxation is focused most heavily on the cheap booze sold in supermarkets and off-licences. Much as we know that heavy drinkers tend to consume strong drinks, we also know that they are more likely to consume alcohol at home or on the street rather than in the pub. A Pub Relief would help ensure that we are not over-penalising low-risk drinkers.

Some of these changes can only be possible outside of European regulations. At present, EU directives force the UK to tax cider and wine according to the volume of the final product – rather than the amount of alcohol the product contains – making it difficult to tax stronger wines and ciders more heavily than weaker ones. Pub Relief is also impossible within the constraints of EU regulation, which do not allow tax to vary according to where a drink is sold. If Brexit finally happens, politicians will be desperate to show the benefits of being unshackled from EU rules. Using Brexit to tackle the UK’s drink problem wouldn’t be a bad place to start.