A year on from COVID-19 being declared a worldwide pandemic, the UK has consistently placed high up in the global league tables of declared cases and deaths. But why has the health impact of the pandemic been so severe? What role have pre-existing health inequalities played? Our most recent Ask the Expert event, held in partnership with UK Research and Innovation sought to answer these questions, with our panel of experts Professor Vittal Katikireddi, the Health Foundation’s Dr Jennifer Dixon and the NHS Confederation’s Joan Saddler OBE.

“The UK has had a relatively bad pandemic, until recently – much of that is driven by what was going on beforehand”, Professor Vittal Katikireddi told the SMF. Factors including Brexit and austerity have distracted the UK’s preparedness for health emergencies. Meanwhile, health inequalities – the differences in health status, access and quality of care, behavioural risks to health, and the wider determinants of health – are deep-rooted in our society. These impact different groups in different ways and can be determined by socio-economic status, sex, ethnicity, disability, and the region in which you live.

How have health inequalities fed into the course of the crisis? Professor Katikireddi highlighted that segmenting by different characteristics reveals varying direct and indirect harms from the virus. In terms of those harms resulting from infection with the virus (direct harms), the number of COVID deaths in the most deprived areas is almost double the number of deaths in the least deprived areas. In Hartlepool, the site of an upcoming by-election, the age-standardised COVID death rate is 27% higher than the English average, as recent SMF research has shown, reflecting the town’s poor performance in national league tables for ‘lifestyle’ risk factors.

Men and women with a diagnosed learning disability are 1.7 times more likely to die with COVID-19. The risk of dying from the virus is also higher among BAME groups in the UK, who are over-represented in more deprived communities and high-risk occupations. In the long-term, those who have been infected with COVID-19 may also suffer from “long Covid”, with symptoms persisting for prolonged periods after the initial infection. In the UK it is estimated that 1.1 million people have experienced “long Covid”, which is more prevalent in those living in deprived areas, women and those in the 35-69 age group. Contracting the virus has also been linked to an increased risk of depression, dementia, psychosis and stroke, and given that those who are impacted by health inequalities are more at risk to the impacts of COVID-19, these diseases may have a detrimental effect on these groups. In short, different people in different places have experienced very different outcomes when infected with the virus.

“There have been a lot of direct harms”, Professor Katikireddi stated, “however separate from that, there have been lots of harms that have arisen due to broader disruption”. Take how the pandemic has impacted mental health. In April 2020, 29.5% of adults reported a ‘clinically significant level of psychological distress’, an increase from 20.7% in 2019. However, despite this increase in reported symptoms of mental health conditions, referrals to mental health treatment declined during the first lockdown. Mental health problems are more commonly found within low-income areas, and so the stretch of mental health services in these communities as a result of austerity may have an impact on the quality of care received. Assessing the scale of the challenge, the Centre for Mental Health has estimated that over 10 million people will require access to mental health services because of the pandemic.

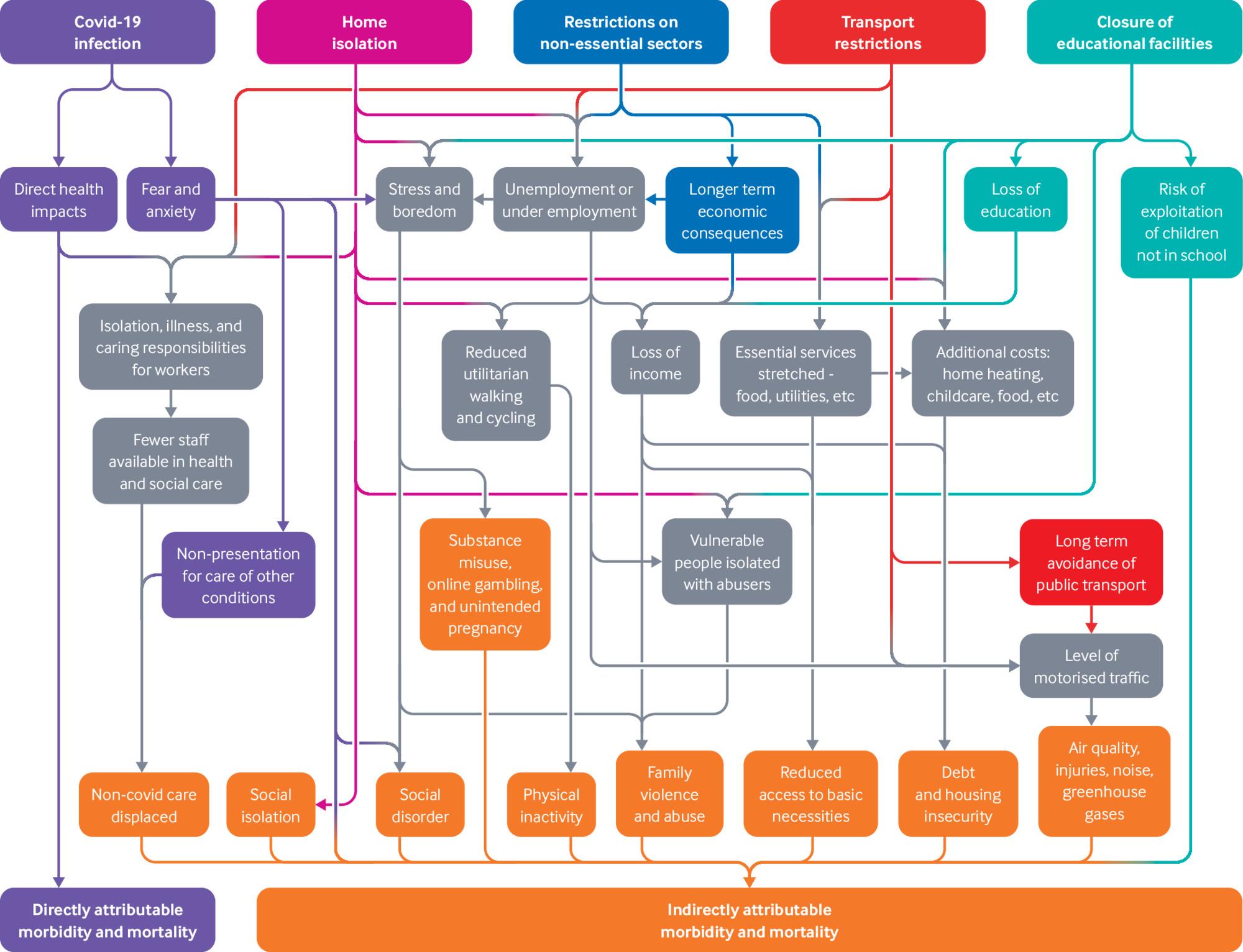

Provision of even basic health care services has been influenced by inequalities. Whilst 70% of GP consultations have been delivered remotely throughout the pandemic, the requirement of a digital device, internet connection and digital skills in order to attend has risked excluding some from primary care services. Those on low incomes or elderly patients are more likely to be impacted by exclusion, leading to “worse health outcomes” than those with access to the necessary technology. Over 2.2 million people in the UK were told to shield during the first lockdown and of these, it is estimated that between 175,000 and 500,000 have no access to the internet. Many of the resources that were recommended to those shielding were online, meaning that many of the most vulnerable during the pandemic would face barriers to accessing support. . The chart below summarises some of the direct and indirect impacts that the COVID-19 pandemic will have and has had on the UK.

Figure 1: Effects of COVID-19 and social distancing measures on health

Source: BMJ

Looking beyond the pandemic, Professor Katikireddi warned that there were “risks on the horizon – major macroeconomic disruption, potentially a recession, which we know that in itself can have big impacts on health, especially mental health.” He also cautioned against a return to austerity and drew on evidence of previous economic downturns leading to “increases in physical and psychological morbidity and mortality, disproportionately experienced by the most deprived communities.” In previous recessions, areas with high unemployment rates have seen a greater increase of suicides, and those living in the most deprived communities have experienced major increases in self-harm and poor mental health. In the COVID-19 Marmot Review, Sir Michael Marmot warned that the pandemic and its restrictions will have a damaging impact on the social determinants of health inequalities both during the pandemic and beyond. As we emerge from the pandemic, this may become evident in the economic impact. The end of the Government’s Job Retention Scheme may lead to increased redundancies and reduced incomes, potentially resulting in people being unable to buy healthy goods and services and affecting the mental health of those trying to manage a low income.

What can be done in the recovery from the virus to mitigate the harms felt by those facing health inequalities? Policymakers “need to think about having a strong focus on addressing inequalities” in their plans to recover from the pandemic, Professor Katikireddi concluded.

Health inequalities cannot be fixed quickly, but the Government could focus on the following strategic priorities to begin tackling them:

- An integrated care system: NHS England has implemented an integrated care system in order to tackle health inequalities. This involves rolling out socially designed systems to improve social determinants of health, such as improving home environments, eviction and homelessness prevention, and alcohol liaison services.

- Investment in public health: Sir Michael Marmot has proposed that public health funding should be increased to 0.5% of GDP.

- A “wellbeing budget”: New Zealand has approached tackling inequalities with a “wellbeing budget”, where wellbeing is built into government policy. The country’s successes are not just measured economically but on key priority areas including child wellbeing, mental health support, skills and opportunities and sustainability.

- National Inequalities Strategy: Sir Michael Marmot has recommended that a national strategy to tackle inequalities should be led by the Prime Minister and focused on developing strategies to reduce social, economic, environmental and health inequalities, and social determinants of health.

As we begin to emerge from the latest lockdown, experts have warned that the UK’s increasing inequalities and high levels of deprivation could lead to ten years of disruption. Policymakers must act swiftly to reduce the inequalities which have led to the severe impact the virus has had on the UK.

This blog is based on a recent SMF Ask the Expert event, held in partnership with UK Research and Innovation. You can watch the event in full here.