Yesterday, the Chancellor announced the "most radical simplification of alcohol duties for over 140 years” at the Autumn Budget. Whether it matches up to the SMF's recommendations - laid out in our 2019 report, Pour Decisions - is worth examining.

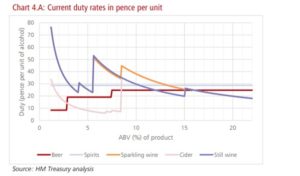

For the six years that I’ve been part of it – and for some time before that – alcohol tax discourse (yes, it exists) has been dominated by one chart. The tangle of lines that makes up the ‘spaghetti chart’, shown below, highlight the dysfunctionality of the alcohol duty regime. Specifically, the chart demonstrates two issues. First, the lack of a consistent relationship between the strength of a drink and how much tax it attracts. Whereas all spirits pay a single rate and stronger beers are taxed more, duty per unit is lower for stronger wines and ciders than those with lower alcohol content (in part because of EU Directives that required the government to tax them by volume not alcohol content). Second, the very different tax rates on different drinks types, with tax generally a bit higher for spirits and a lot lower for cider than beer or wine.

The chaos of the spaghetti chart has long offended the policy wonk’s desire for order and rationality. But it is much worse and much more serious than that. The perverse incentives created by charging less tax on stronger products, and in particular, under-taxing cider, have encouraged the production of a suite of products (particularly ‘white ciders’), that can be sold particularly cheaply because they attract less duty than any other drink. Those products, in turn, are more likely to be favoured by those drinking at harmful levels.

The SMF took on the spaghetti chart, and the structure of alcohol duty more broadly, back in 2019, in our report Pour Decisions. In it, we laid out five recommendations for a reformed system:

- Ensure that stronger drinks are taxed at a higher rate

- Level the playing field between different drinks types of the same strength

- Charge relatively lower duty on pubs, given that supermarkets and off-licences are more reliant on harmful and hazardous drinking.

- Link alcohol duty to the social costs of alcohol

- Ensure that alcohol duty rates automatically rise in line with inflation and/or earnings

In the following year’s Budget, the Government announced its own review of alcohol duty structures, and this week the Chancellor announced the “most radical simplification of alcohol duties for over 140 years”. So how does it match up against our five principles for better alcohol tax?

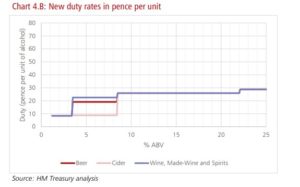

Compared to the unruliness of the spaghetti chart, the new system (below) certainly looks more sensible. All products will be taxed by alcohol content not volume, and rates will go up in a stepwise manner with ABV within each category. That should eliminate some of the incentives to produce stronger cheaper drinks.

However, one important anomaly remains and ensures that the playing field remains tilted – the preferential treatment given to cider, which will continue to be taxed at less than half the rate of beer. The Government acknowledges that equalizing cider and beer duty “would make the duty system even simpler and more coherent”, but it deciding against taking this step because it “is mindful of the significant impact this would likely have on the cider industry”. In other words, it refuses to eliminate the arbitrary advantages of the old regime because this would be bad for those that benefit from those arbitrary advantages. The upshot is that tax on high strength ciders has gone up by around 2p per unit, but it will continue to be one of the least taxed products on the market.

With the SMF having been the most prominent organisation calling for differential duty rates between pubs and supermarkets, it is pleasing to see the Chancellor announce a lower rate of duty for draught beer and cider. This isn’t exactly the same as our proposed ‘pub relief’ scheme – it doesn’t cover wine and spirits sold in pubs, and there are some doubts over whether smaller brewers will benefit – but it is pretty close in effect. It is also considerably more modest than some of the options we modelled. Where the Government has only cut duty for pubs by 5% more than the off-trade, we estimated that a 75% discount for pubs, offset by a 34% increase in off-trade tax rates could reduce overall alcohol consumption by 6%.

Despite the Chancellor’s promise of a “healthier” duty system, his Budget announcements fall short furthest on the fourth and fifth of our principles: ensuring that duty rates are proportionate to the social harm of alcohol, and that they keep pace with inflation. We don’t have a robust recent estimate of the societal costs of alcohol, but in 2010 the Government estimated them to be £21 billion, compared to an alcohol duty take of around £12 billion. Meanwhile, (in a process that mirrors the decade-long freeze in fuel duty) cuts and freezes to alcohol duty have become the norm, with duties being raised in line with inflation in only one Budget since 2012.

In that context, the decision to freeze alcohol duties yet again (and thus impose a real-terms reduction in their value) may be the most consequential decision on alcohol duty in this week’s Budget. General beer duty is now 28% lower, accounting for inflation, than it was in 2012/13, while spirits and cider duty are down 21%. The Sheffield Alcohol Research group estimate that around 2,000 people died as a result of Budget decisions on alcohol duty between 2012 and 2019, back when the value of beer duty had only fallen 18%.

Some observers seem to have been bemused by the amount of attention alcohol duty received in this week’s Budget. Yet the duty review was a once in a generation opportunity to remove the anomalies in a system that was not just irrational but literally deadly. The Budget announcements made some progress in ironing out those kinks, but the preferential treatment of cider and the persistent failure to ensure that rates keep up with inflation mean we remain some distance from a duty regime that effectively targets and addresses harmful drinking.