Aveek Bhattacharya examines possible policy suggestions that can be used to respond to the mounting cost-of-living crisis. Evaluating each, he finally calls on Rishi Sunak's Treasury to give direct cash transfers to households to give them the power to best decide how to respond to rising costs.

We are barely a couple of weeks into 2022, but it is already clear that one of the biggest challenges facing the Government this year will be the brewing ‘cost of living crisis’, set to come to a head in April. The main cause is higher energy bills, with the lifting that month of the price cap that has so far largely protected consumers from a spike in global gas prices. Analysts predict that household energy costs could rise by around 50%, from a maximum of £1,277 to over £1,900 a year. Most households will also start paying higher taxes from April, as the Health and Social Care Levy, changes to income tax thresholds, and potential council tax rises kick in. That comes on top of climbing inflation, which is expected to push the cost of everyday goods and services up by 6%.

Proposed responses are overcomplicated and store up problems for the Government

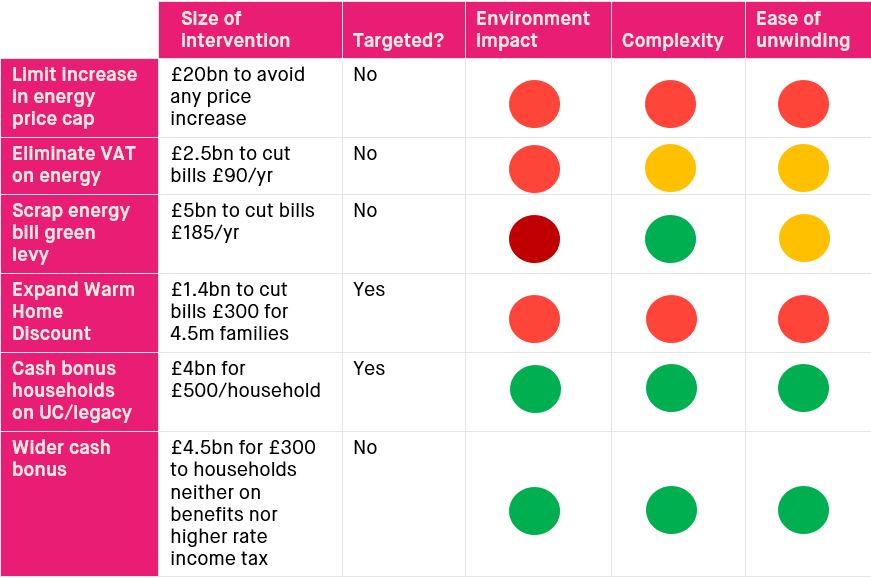

Policy wonks have explored a number of ways the Government could respond. It could limit any increase in the price cap and support energy companies directly through taxpayer-funded grants or loans. The Labour Party has called for VAT on energy – currently 5% – to be eliminated. Others have suggested removing green levies, which cost the average household around £185 a year, from energy bills. An idea that has attracted particular interest is expanding the Warm Home Discount (WHD). At present, this provides around 2.2 million low-income households with a reduction of £140 per year in their energy bills, funded by higher bills for more affluent households. A ‘core group’ of the poorest pensioners is eligible by right, and energy suppliers have a quota of discounts they can offer to other low-income households at their discretion. However, to address the current crisis, the WHD would need to be increased in value and extended to more households.

However, these options all share a common drawback. By making gas and electricity cheaper, they encourage energy consumption – which is undesirable from an environmental perspective. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has previously questioned the rationality of a system in which carbon emissions from domestic fuel consumption are already “effectively subsidised”. We should try to avoid measures that makes this situation worse.

By focusing narrowly on reducing energy costs, these options are also somewhat limited in their flexibility to address other elements of the cost-of-living crisis. For some households, addressing higher food or clothing costs could be as pressing as help with energy bills, particularly in light of the unpredictability of future prices. Of course, money saved on domestic fuel can be used to pay down other expenses, but it is an indirect way of addressing the problem, particularly since evidence shows that patterns of household spending can be influenced by the design of subsidies. Just by its name, the Winter Fuel Payment makes people more likely to spend it on energy.

Taking a sector-specific approach has further dangers, creating complexity and opening the government up to arguments that other products deserve similar special treatment. Eliminating VAT on energy, in David Gauke’s words, undermines “one of our more efficient and better designed taxes”, already subject to too many exemptions. It also risks creating, as he puts it, “a long queue of industry bodies arguing that the answer to any particular problem requires a reduced or zero rate of VAT for their particular sector”.

Many of these measures may also prove difficult to unwind, leaving the Government on the hook for an ongoing cost even once the worst of the crisis has subsided. As the fierce resistance to the ending of the temporary £20-a-week increase in Universal Credit last year demonstrates, people become accustomed to and come to rely on measures that increase their regular income or reduce their regular costs, even if they were only intended to be short-term measures.

The Government should focus instead on cash relief

For all these reasons, the Government should prioritise a programme of cash transfers when it comes to helping people through the cost-of-living crisis. Such a scheme could be targeted at the worst-off households, for example by making an additional payment to people on Universal Credit or other legacy benefits. The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change estimates that the poorest 10% of households are set to see their income fall by 4.0% in April, compared to 1.8% for the average household. A £300 cash payment would reduce this to 2.5%; a bigger cash payment (say, £500) would achieve even more.

Alternatively, the programme could be designed to help a wider swathe of households, perhaps on the model of the US pandemic stimulus payments, which were paid out to all but the highest earners. After all, those in the middle of the income distribution will be facing a pretty significant hit to their living standards too. It might be possible to do both – a smaller cash payment to most households, topped up with a bigger payment for the poorest.

However designed, cash payments would have the benefit of avoiding the distortions and environmental costs of subsidising energy. Instead, they would allow households to decide for themselves how best to adjust their spending in response to shifting prices. Cash payments could also more easily be presented as a ‘bonus’, a one-off emergency measure to address a temporary challenge, limiting the risk of the Government committing itself to recurring spending it finds it difficult to roll back.

From a political perspective, directly giving people money has the significant merit of being a highly visible demonstration that the Government is taking action to help cash-strapped families. If nothing else, this Government has shown genuine flair for branding programmes. It’s not hard to imagine the fun its comms team could have with “Boris’s Bill Buster” or “Rishi’s COLA (Cost of Living Assistance)”, replete with photo ops of the Chancellor and his trademark can of coke.

At present, it is unclear how quickly or easily the Government could make direct cash payments to millions of households. The experience of the US indicates such a programme is feasible. The American tax authorities made direct payments into people’s bank accounts; here, the bonus might be added as a line item in people’s payslips under the Pay As You Earn system. As in the US, prepaid cards or cheques could be delivered to other households with addresses known to HMRC or DWP – the Chancellor might want to steal a move from Donald Trump’s playbook and sign the cheques himself (at least we can be sure he has an automated signature prepared).

If it doesn’t already exist, developing a direct payments infrastructure like this could be invaluable in responding to future economic downturns. The economist Claudia Sahm has argued that governments should automatically disburse cash to stabilise demand when key indicators suggest the economy is in recession. Right now, we have a few months to prepare before the worst of the crisis hits – a luxury typical recessions don’t provide.

There is a major risk with a large-scale cash transfer programme: that it exacerbates rising inflation. This is a particular worry if the payments are provided in a single lump sum: dropping several billion pounds on the economy in a single month could drive up demand very quickly, and cause inflation to rise further if supply cannot keep up. It may therefore be better to split the payments into a couple of tranches, perhaps to stagger them and to delay them as far as possible until later in the year, without causing households to fall into acute financial difficulties. The size of the payment should also be calibrated so as to be appropriate to the macroeconomic circumstances.

Figure 1: Proposed Responses to the cost-of-living crisis

Source: Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, FT, SMF analysis