In this post, we reflect on our recent Ask the Expert event on the future of small businesses after the pandemic, held in partnership with UK Research and Innovation.

Britain’s “productivity puzzle” is a well-known and sorry tale with no clear end in sight. Growth in output per hour worked has stagnated since the financial crisis, regularly dipping into negative growth over the last decade, as the chart below shows. Britain is not alone in this trend – output per hour has slowed across the G7 in recent years – but our productivity slow-down is more pronounced, with only Italy behind us.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have been at the heart of the productivity discussion.[1] At the start of 2020 there were 5.97 million of them, making up 99.9% of private sector firms and employing almost 17 million workers (61% of the total). The SME sector has witnessed remarkable growth over the last decade, with a 22% increase in the total number of SMEs.

However, a significant segment of these firms have not exhibited strong productivity growth. They are often referred to as the ‘lower tail’, who, as Andy Haldane famously put it in a 2018 speech are ‘snailing along the low road’. OECD data evidences this, showing a marked labour productivity gap between large firms and less productive ‘laggard’ SMEs in the UK. A similar trend is observable in innovation activities – a key driver of productivity – with the most recent UK Innovation Survey showing 38% of SMEs were innovation active, compared with 49% of large businesses (though innovation as a whole declined across all business sizes 2016-2018 compared to 2014-2016) Collectively this has led some academics, such as Isabelle Roland from the Centre for Economic Performance, to suggest that it is unclear whether SMEs do much to even drive economic growth.

There is no shortage of proposed cures for Britain’s productivity problem. Equally, there is no silver bullet. One particular area of interest is in technology uptake amongst SMEs. To be more specific, what really matters is translating frontier innovation into the widespread adoption and penetration of productivity-enhancing technologies. Andy Haldane has called for a ‘diffusion infrastructure’ to facilitate this and stimulate productivity gains. Echoing his sentiments, a 2019 letter to the Prime Minister from the Council for Science and Technology recommended creating a National Centre for Productivity designed to perpetuate technology adoption and ‘close the gap with those at the cutting edge’.

No one – not least the co-signatory of the letter, Sir Patrick Vallance – would have recommended a pandemic as a way of increasing technological diffusion, but COVID-19 may bring a silver lining in terms of addressing this much-discussed problem.

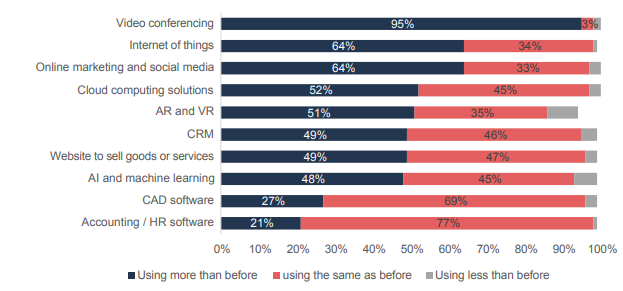

Data from the Enterprise Research Centre’s Business Futures Survey (Q4 2020) – presented by Dr Anastasia Ri and Dr Effie Kesidou at our recent Ask the Expert event – provides some of the most up-to-date evidence. Overall, 62% of SMEs said they increased their tech uptake during the pandemic. Some changes are unsurprising: 95% of respondents reported using more video conferencing than before. Other trends could be more fundamentally transformative. For example, more than 50% of businesses said they were now making more use of cloud computing, the Internet of Things, and online marketing and social media.

Changes in the intensity of use of digital technologies (percentage of users)

We might reasonably infer from this that many businesses in the “majority middle” – the 60% of firms in the median level of productivity – are making greater use of technology since the pandemic began. As a report from Be The Business highlights, these firms all have the potential to benefit from new technologies, but may have lacked the managerial quality, motivation or finance to adopt them in the past. Even a small shift in technology diffusion amongst these firms could lead to ‘significant’ economic benefits, the report argues.

The pandemic has essentially taken this decision out of business’ hands: the uptake of new technologies has become a matter of survival for firms whose conventional trading practices have been disrupted by COVID-19. Whilst before the pandemic, 53% of SMEs firms were selling online (Going Digital, 2019), the ERC found almost three quarters of SMEs now participate in e-commerce activities. In short, firms in hard-hit sectors have been forced to react. And, whilst there are on-going calls for further grants and a German-style reimbursement scheme for lost trading, the Government has no doubt done a good deal to facilitate tech uptake through the 100% state-guaranteed Bounce Back loan programme.

Of course, many businesses have already failed – Q2 2020 witnessed a 39% increase in insolvencies compared with Q2 2019 – and many more could yet follow suit. And on top of that, it will be difficult to disentangle the impact technological diffusion has on productivity from the wider disruptions to the market. Nevertheless, the ERC highlight that 38% of firms reported increased innovation activity during the pandemic and 71% said tech uptake had in some way influenced their business model. “We think this is probably a pivoting point”, Dr Anastasia Ri from the ERC told our recent Ask the Expert event. “Business which were reluctant to adopt more tech in the past…now see better benefits of introducing new technologies”.

If this is a pivotal moment for digital diffusion amongst SMEs, policymakers and firms should move to consolidate and reinforce any gains made during the pandemic. One option could be to exploit the link between management capabilities and technological diffusion. Evidence shows firms that are better managed are generally more productive but are also more likely to reap the productive benefits of technological adoption. Yet it is larger firms who display better management practices and it is widely acknowledged, for example in this research from the ERC, that SMEs are poorly managed, especially those firms in the ‘long tail’ and ‘majority middle’.

Whether it is government or firms themselves investing in management training, doing so could catalyse the associated benefits of technology diffusion brought on by the disruption of the pandemic. Small steps have already been taken, for example through the Government’s Business Basics Fund, but there is much more that could be done. For example, Government may look to boost the offering and accessibility of management training and digital skills through the adult education system. Equally, policymakers might consider further how high-growth firms can share managerial best practices with laggard businesses, particularly those who have recently invested in technology during the pandemic.

This post is draws on a recent SMF Ask the Expert event – held in partnership with UK Research and Innovation. We were pleased to welcome Dr Anastasia Ri and Dr Effie Kesidou to present research from the Enterprise Research Centre. The ERC’s Business Futures Survey was carried out in Q4 2020 and includes findings on SME attitudes to digital adoption and environmental practices, as well as how SMEs have been impacted by the pandemic.

[1] SMEs defined as a business with between 0-249 employees.