Artificial intelligence might not deliver the economic gains expected by the Treasury any time soon. And if it does, writes Bill Anderson-Samways, growth might be the least of our concerns.

In 1980, the business professor Julian Simon made an infamous bet with professor of population biology Paul Ehrlich. While Simon foresaw technical innovation producing economic growth unencumbered by environmental limits, Ehrlich predicted increasing resource scarcity. Simon wagered Ehrlich $10,000 that the prices of five resources would decrease over the next decade. The wager responded to one of Ehrlich’s previous claims, which described the stakes involved in resource scarcity as existential. “If I were a gambler”, he had written, “I would take even money that England will not exist in the year 2000”.

Of course, Ehrlich was wrong on both accounts. Simon won the bet, and Ehrlich lost his money.

The UK Treasury appears to be making a similar wager. In his February Mais lecture, the former Chancellor of the Exchequer recounted a recent bet of $400 between two Stanford professors – Robert Gordon, who believes that economic growth is stagnating, and Erik Brynjolfsson, who believes that Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a General Purpose Technology (GPT) that could underpin the next growth explosion. Mr Sunak concluded, “I am an optimist, and I’m with Brynjolfsson”, hoping that stronger AI (among other things) will “accelerate” growth and thus (presumably) deliver fiscal benefits to the Treasury.

I think that’s a mistake, and that the case for (perhaps self-imposed) “limits to growth” is stronger than Ehrlich’s in 1980. In essence, there is potentially a trade-off between developing more powerful and economically transformational AI, and managing the dangerous risks such a potent technology would bring. On the one hand, weaker forms of “narrow” AI may not deliver the degree of economic growth expected by the Treasury. Meanwhile, if some well-tested economic theory holds true, it’s plausible that stronger forms of narrow AI would deliver economic growth gains, but not the fiscal benefits hoped for by HMT. On the other hand, the main form of AI which economists believe could overcome these difficulties – “general” AI – poses risks which could be more existential for humanity than those envisioned even by Ehrlich. And the line between strong narrow and general AI may prove too fine for comfort.

All this means that betting on AI is risky, in more than one sense. Rather than losing ourselves in fantasies about an imminent age of AI-led growth, we should pursue more responsible and gradual AI development in order to ensure that we can (eventually) enjoy the technology’s social and economic benefits. That means diverting resources towards investment in AI safety – an area in which the UK has enormous potential. When a new Chancellor is appointed to the next PM’s cabinet, they should take the opportunity to instigate a policy reset here.

Narrow AI – an economic miracle?

Narrow AI refers to any intelligent system that can undertake some specific task (rather than all tasks that humans can execute). Driverless cars and facial recognition systems are good examples.

On the one hand, it’s possible that narrow AI may simply fail to deliver the levels of economic growth hoped for by the Treasury. Scholars such as Robert J. Gordon believe that modern-day General Purpose Technologies (GPTs) are becoming increasingly less “general-purpose” compared to previous GPTs such as electricity. Total factor productivity growth has been slower during the internet age than during prior technological revolutions. If Gordon is right about this trend, then it’s at least plausible that AI could deliver lower growth gains than the internet, contrary to what Mr Sunak hoped. The point here is not to suggest that significant economic gains from AI are unlikely, merely that they may not be as inevitable as is often suggested.

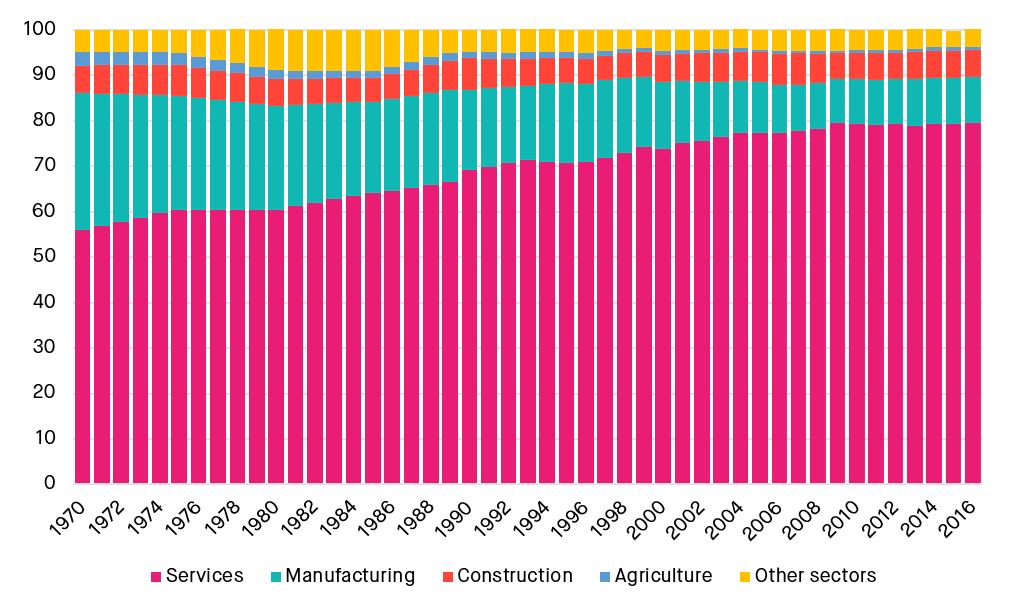

A well-proven economic theorem, the “Baumol effect”, may help to flesh out the reasoning here. Its namesake, the eminent economist William J. Baumol, posited that the quality of many services depends directly on the human labour-time spent on them. For example, although it may be possible to automate the production of music, a live concert performed at double the speed would, to quote Baumol, probably “be viewed with concern by critics and audience alike”. The UK economy is now dominated by services (see Figure 1). Although many of these – from assistant work to animation, and even some R&D – can be automated, Baumol effects may explain why infotech has thus far proved less cross-spectrum than prior GPTs. And as we can see, the service sector’s share of GDP is growing.

Figure 1: Gross value added (GVA) shares of different industries, United Kingdom, 1970 to 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics

Of course, this theory could well be wrong. Many scholars think it likely that we will achieve “strong narrow” AI that proves more general-purpose than the internet, with complementary applications across huge swathes of the economy. That would certainly deliver high near-term economic growth.

However, Baumol effects may impose limits on what such growth can achieve. Another element of Baumol’s theory is that the things which are hardest to automate may also be those for which demand is most “elastic”. For example, there appear to be very few limits to our demand for education and healthcare – two of the hardest-to-automate services. (We could certainly automate parts of them, such as surgery, but there are most likely limits to this). If demand for easier-to-automate services proves to be relatively inelastic, meanwhile, then over time GDP will become dominated by those hardest-to-automate things which we want the most – such as education and healthcare. Indeed, as the Nobel-prizewinning economist William Nordhaus has demonstrated, that’s exactly what happened in the past half-century: hard-to-automate but demand-elastic services have increasingly dominated GDP, while easy-to-automate but demand-inelastic agriculture and manufacturing have declined (see above graph). Nordhaus’s work also supports Baumol’s theory with respect to AI and infotech, although in the past thirty years these sectors have grown in their share of GDP simply because they are new.

If true, Baumol’s theory would have two important consequences here. Firstly, any major growth gains from automation may eventually peter out as the economy becomes ever-more dominated by low-productivity services in the long-run. More importantly for current policymakers, services such as education and healthcare would expand in step with GDP. So we’d get high growth – but not the fiscal benefits hoped for by the Treasury.

Again, it’s very possible that this intuition is incorrect – and of course growth can be desirable for reasons other than its fiscal benefits, not least because in this case it would enable us to buy more healthcare and improve our welfare. However, there are also other reasons to be wary of strong narrow AI. The potential for catastrophic accidents, misuse, or more “systemic” risks are real. More worryingly still, strong narrow AI may well provide the shortest possible pathway to general AI – and that could be a very dangerous prospect indeed.

The limiting case – general AI

General AI provides a “limiting case” in which Baumol’s theory wouldn’t hold. A general AI could do all tasks – including those activities that currently seem very difficult to automate – more efficiently than a human being. There would be few limits to service sector productivity under such a scenario.

We might therefore be tempted to regard such an AI as a source of potentially limitless growth. However, if this AI arrived in the near future, growth rates might be the least of our concerns. The AI could well be extraordinarily dangerous for humanity. Here’s why.

An AI which could undertake all human tasks would be able to generate and implement new ideas, including those regarding the development of AI systems. Such an AI would therefore be capable of improving itself – and probably far more rapidly than the scientists who initially developed it. An AI (unlike human minds) could operate unencumbered by physical constraints on brain capacity and speed, applying huge amounts of computing power working at digital speeds to its own development. Whatever goals we have programmed into the AI, greater intelligence will almost always be an advantage in achieving them, so the AI would have a strong incentive to improve itself under most circumstances.

We could therefore find ourselves confronted by an intelligence many orders of magnitude greater than our own: a “superintelligence”.[i] Stuart Russell, perhaps the world’s foremost expert on AI, calls this the “gorilla problem”. The analogy is that despite the relative intelligence of gorillas compared to other animals, human beings are rather more intelligent still than our hairy cousins – and that hasn’t turned out especially well for the gorillas. Things get even scarier when we consider that the intelligence gap between a superintelligent AI and human beings would probably be more akin to the difference between yourself and an ant or a worm. This would clearly be pretty perilous for humanity.

Unlike in science fiction, most serious researchers do not believe that AI will “turn evil”. Instead, a major risk (out of several possible kinds) is that a superintelligent AI could destroy human beings for more instrumental reasons. As Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom details, whatever goals we program into the AI, a number of things are likely to help it achieve that goal as efficiently as possible. This includes not only greater intelligence but, for example, the elimination of threats to its own existence, the development of powerful but dangerous new technologies, or the acquisition of ever-greater amounts of resources (an easy task for a superintelligence, given that relatively-unintelligent humanity has made big strides in that direction). We could therefore find ourselves – like the gorillas – facing a far superior intelligence pursuing goals which directly conflict with our own survival.

Lest all this seem like fringe catastrophism, note that such existential risks from AI preoccupy many of the world’s foremost experts in the field – like Russell – as well as those who are otherwise optimistic about AI’s potential benefits, like Brynjolfsson. And the “control problem”, namely the matter of stopping the AI from harming human values, is much more difficult to solve than it might seem. In fact, we’re nowhere near solving it at the moment.

What does this all mean for economic growth? Well, it suggests that – if general AI arrives in the sort of timelines that concern the Treasury, namely in the next decade or so – then there’s a strong possibility that it could wipe us all out well before we even have time to enjoy any potential growth benefits. You may be relieved (or not) to hear that there is enormous uncertainty surrounding the timelines for general AI. Most experts don’t think it will arrive in the next decade. But estimates vary wildly: we just don’t know.

Of course, the Treasury is probably not betting on general AI. I am merely suggesting that the limiting case for the Baumol effect is, in the near term, certainly nothing to look forward to. In any case then, our central point still stands. We should be pretty cautious about investing in AI in the hope that it will bring in big economic dividends any time soon.

Conclusions and policy implications – AI within limits

To sum up, if Baumol’s theory is correct, there may be limits to growth with artificial intelligence. Essentially, the extent to which AI delivers economic and fiscal benefits depends upon its degree of generality. Indeed, it’s plausible that the only technology which could deliver both high GDP growth and fiscal benefits (overcoming the Baumol effect) is truly general AI. However, such an AI is either (a) somewhat far off in time or (b) extraordinarily dangerous for humanity, to the extent that growth should really be the least of our worries.

How should policymakers respond? The biggest policy implication appears to be a significant blow to the economic case for R&D investment in enhanced AI capabilities. Of course, there may be a non-economic case for specific narrow AI R&D investments, for example given the potential welfare benefits from AI-driven improvements in healthcare. But these should be balanced against the risks associated with more general AI. In any case, policymakers should be cautious of promoting high levels of AI R&D spending as a form of growth strategy. Instead, they would do better to alter macroeconomic policy in preparation for a near-term future of low growth – which by no means has to be a bad thing.

Meanwhile, we should ramp up investment in solving the control problem. If and when superintelligence does arrive, we should be prepared. In fact, once we stop thinking about “competitiveness” in terms of economic growth, it appears that the UK is particularly well-equipped to become a world-leader in the safety field. The UK’s National AI Strategy has a strong focus on responsible AI innovation. Meanwhile, the country already hosts world-beating AI safety institutions such as the Alan Turing Institute and the Ada Lovelace Institute, alongside leading organisations on AI governance such as GovAI, the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford, and the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at the University of Cambridge.

The Baumol effect is sometimes referred to as “Baumol’s cost disease”. Some policymakers may be tempted to overcome that “disease” through accelerating the development of general AI. Nothing could be more misguided. As long as we have no idea how to administer it, this so-called “cure” would be infinitely worse than the supposed ailment. Far better to respect our own limits, and work out policies to deal with them. Economic adaptation is preferable to self-destruction.

Notes

[i] It’s also worth noting that, even if cross-spectrum automation didn’t lead inexorably to superintelligence, the complete replacement of human beings with AI would deliver extreme levels of growth but only for a very small number of people, assuming that a fraction of human beings still “owned” the machines.