In the latest of the SMF’s Ask the Expert series, our panellists were asked to consider whether the UK’s two-party system would remain intact as we enter a new decade of British politics.

Our panellists were:

- Professor Roger Awan-Scully, Professor of Political Science and Head of Politics and International Relations, Cardiff University

- Paula Surridge, Senior Lecturer, School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol

- Stephen Bush, Political Editor, New Statesman

Crystal balls are usually to be avoided when it comes to general elections. But at present – with less than two weeks of the campaign to go – the glass appears fairly clear: the two main parties have pulled away in the polls, the Conservatives are on course for a majority, and support for the smaller parties has largely stagnated or collapsed altogether.

At least superficially, then, there isn’t a great deal to suggest that the two-party system is about to splinter. But our panellists felt there was plenty more to this than meets the eye.

Remember the devolved nations

It’s striking that when we talk about a two-party system, Roger Awan-Scully told our audience, it only really applies to two of the four nations in the Union. Northern Ireland operates within its own electoral microcosm, whilst most Scottish voters are left with the binary choice between the Conservatives and the SNP.

Labour’s remarkable demise in its former northern stronghold means that Scotland is now treated as a very separate component of a general election. Ruth Davidson’s 2017 campaign, run almost entirely detached from events south of the border, set a new precedent and Stephen Bush speculated that the resilience of the Scottish Conservatives might surprise people again in 2019. That’s partly because the Scottish Conservatives have become the Leave option of last resort, but also because independence has once again surged up the issues ladder.

Even in Wales, the two-party system has its inconsistencies. The Conservatives last won an election in Wales in 1859 and only six months ago the Labour Party came third in the European Parliament Elections. Plaid Cymru’s support base appears to be holding relatively firm in the run up to polling day, although support for Labour, in particular with younger voters, is on the rise.

What happens to the Liberal Democrat vote matters

The Lib Dem strategy from the outset was to siphon off Remain votes from both the main parties and proclaim the dawn of a three-party system. But it is widely perceived that the Lib Dem campaign has failed to gather any momentum, despite polling indicating a sizeable cohort of voters who don’t like Brexit and don’t like Jeremy Corbyn.

Why haven’t the Lib Dems brought these voters on board?

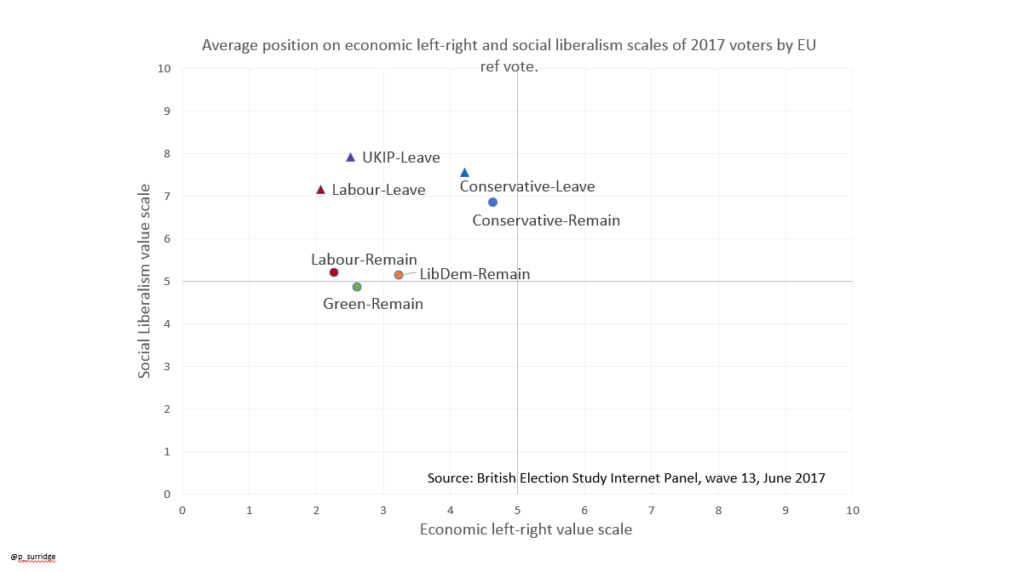

Paula Surridge suggested that the interaction between voters’ Brexit position and their wider political values forms part of the answer. “People have to make choices” and voters’ political values can often prove irreconcilable with their Brexit position, preventing them switching to alternatives like the Lib Dems.

The value chart above helps to explain this. Labour Remainers, for example, may align closely with the Lib Dem’s position on Brexit, but their position on the economic left-right scale tends to prevent them from voting Lib Dem.

Stephen Bush added that when it comes to the ballot paper, voters also look at the effectiveness of the levers used to either stop Brexit or stop Jeremy Corbyn: the red lever is most likely to halt Brexit and the blue lever most likely to stop Corbyn. The Lib Dem lever, despite bearing the official “Stop Brexit” tag, doesn’t prove to be particularly effective.

Roger Awan-Scully pointed to the example of Cardiff North, often indicative of which party will win the election. It voted heavily to Remain in 2016 and returned a pro-EU Labour MP in 2017; the Lib Dems lost their deposit.

A two-party system on shallow roots?

Despite the two-main parties clearly dominating in the polls, the 2019 election could well produce a peculiar outcome whereby the Conservatives only gain a relatively slender majority even with the Labour Party taking a meagre 200 seats. In the past, that could easily have been a majority of over 100, Stephen Bush argued. Ultimately, this is down to smaller parties chipping away at the roots of the two-party system.

Voter volatility is key to explaining this. Just one in ten voters now profess a strong loyalty to a party. Both Paula Surridge and Roger Awan-Scully made the case that new sources of political identity, notably Brexit and national independence, have disrupted the two-party system and produced some psepholical milestones, most notably the 2019 European elections.

Crucially, however, in a general election other issues rise in voters’ considerations – not least what is happening specifically in their constituency – and the left-right axis seems to be holding relatively firm and will translate into support for the two major parties.

That means that come the morning of 13 December, only Boris Johnson or Jeremy Corbyn can realistically become Prime Minister. But it is important to remember that the two-party system is eroding and the chance of a blue or a red landslide seems to be lessening.