The past few days have been astonishing, for many reasons. The coronavirus, Covid 19, has shoved the economy into what is almost certainly a deep recession, and cherished civil liberties have taken second place across the globe as lockdowns have been implemented to curb the spread of the virus.

Many of us have even been presented with food shortages for the first time in our lives amid widespread panic buying. Some supermarkets have run out of some food as well as other essentials such as toilet paper (seemingly the most important commodity in a crisis). Even now, several days on from the start of panic buying, items such as eggs, potatoes, bread and chicken have been hard to come by in parts of the country.

Emotional videos have been doing the rounds in the news and on social media – of frightened elderly people and NHS workers unable to purchase food for themselves or their families. The retail industry insists there is enough food overall, but that does not mean there is enough food everywhere: empty shelves and worried households are a sign that the distribution networks that should deliver food where and when people need it are not working as they should.

If, in a matter of days, supermarkets can be gutted of food, are there other risks to food security that we ought to be taking more seriously?

What does all this say about the resilience of Britain’s food supply network?

The fragility of global supply chains

Alongside panic buying, the coronavirus crisis has raised questions about the fragility of the global economy and the just-in-time, complex supply chains that underpin so many goods and services – including food. Free trade and a reliance on food from faraway places is fine when the security of supply chains is guaranteed. But have we become too relaxed about the prospect of these supply chains breaking down, possibly quite rapidly, when “black swan” events such as pandemics occur? If societies can be locked down in a matter of days, and trade reined in, should we be thinking much more about building more resilience into our food and other supply chains?

For decades, the UK has been reliant on food from overseas to feed the nation, and since the 1980s we have become even less self-sufficient. In 1984, the food self-sufficiency ratio1 stood at 78%. On the latest data it is about 60%. The National Farmers’ Union pointed out last year that if we had only eaten British food from the 1st January in 2019, we would notionally have run out of food by 11 August 20192.

While free trade brings with it clear advantages – such as the ability to access cheaper produce as well as foods that simply cannot be produced in the UK – there are inherent vulnerabilities. In addition to pandemics, climate change and trade wars could threaten the fine chain of events that bring products to UK supermarkets.

The question now is how do we build more resilience into global supply chains without retreating into protectionism – something which would probably lead to higher consumer prices and risks of its own to food security. A bad harvest in the UK is not an issue if produce can be imported from elsewhere. It’s potentially a catastrophe if we start to discourage food imports. Balance, therefore, needs to be struck.

The debate on food security and self-sufficiency is set to step up a gear once the dust settles from our current crisis. That may be good news for UK farmers, who are set to become much more revered in government circles, and in the eyes of the public, following our recent experiences.

Existing food security issues

It’s also worth pointing out that, while food insecurity has emerged as a new issue for many of us in recent days, a large proportion of the population has been grappling with it for years.

An SMF study from 20183 found that for just under a fifth (17%) of UK households, groceries put a strain on their finances. A quarter (23%) of individuals surveyed said that they bought cheaper and less healthy food due to such financial strains.

And it’s not just unaffordability of food that has undermined food security for many households, but also limited access to food. Our research showed that many individuals live in “food deserts” – areas which are poorly served by food stores. In these areas, individuals without a car or with disabilities that hinder mobility may find it difficult to easily access a wide range of healthy, affordable food products. Unable to access supermarkets, they might be left with no option but to buy food from small convenience stores and newsagents – where food is often more expensive, and fresh, healthy options more limited.

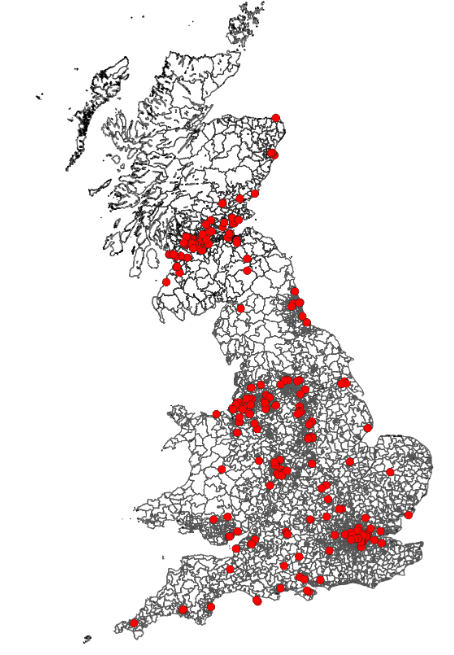

Figure 2: Map of deprived food deserts in Great Britain

We estimated that 10.2 million individuals in Great Britain live in food deserts. Of those 1.2 million live in deprived areas, where car ownership tends to be lower and public transport is often poor. One in eight (12%) of the individuals we surveyed in our research stated that “not being near a supermarket offering healthy food at low prices” was a barrier to being able to eat more healthily. The challenges of accessing a wide range of fresh food that some people have experienced in recent weeks are, sadly, a fact of life for many of the poorest people in the UK.

When we come to debate future food security after the crisis and perhaps design a better way of ensuring secure reliable food supplies for all, it is imperative that the needs of the poorest are not forgotten.

To discuss this or other work, contact the author via scott@smf.co.uk

Footnotes:

1. The self-sufficiency ratio is calculated as the farmgate value of raw food production divided by the value of raw food for human consumption in the UK; it is thus a gauge of how easily we can “feed ourselves” as a country.

2. https://www.farminguk.com/news/farmers-warn-of-uk-food-self-sufficiency-decline_53657.html

3. https://www.smf.co.uk/publications/barriers-eating-healthily-uk/