Rishi Sunak’s government has repeatedly committed itself to fiscal responsibility. Yet that rhetoric of discipline is at odds with reports that Chancellor Jeremy Hunt is considering the largest unfunded fuel duty cut in British history.

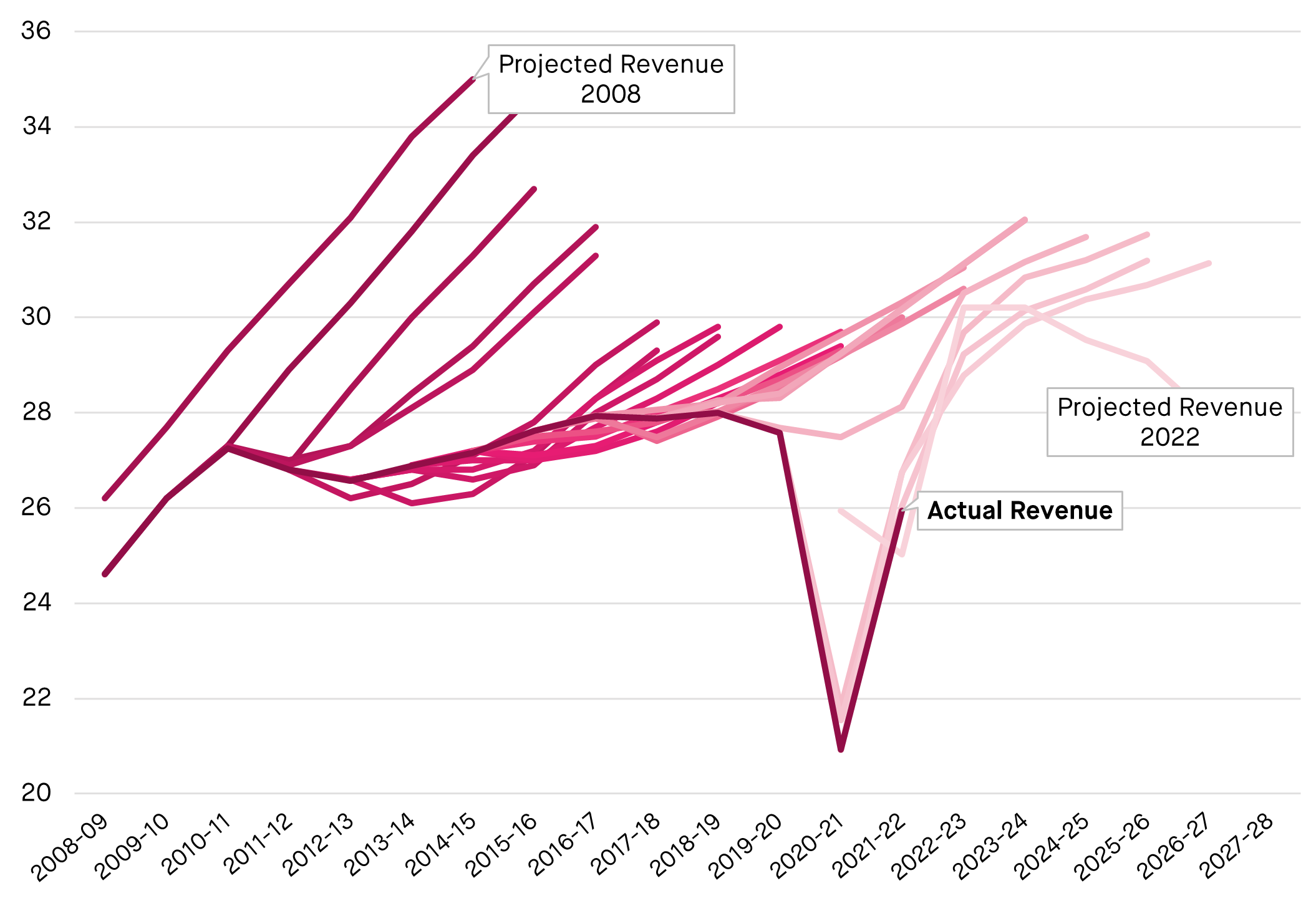

Though the Government’s budget plans – and therefore the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) modelling – assume that fuel duty will rise in line with inflation each year, fuel duty rates have actually been frozen at their 2011 level for the past twelve years, eroding their value in real terms. Losses have steadily accumulated as successive chancellors have followed George Osborne’s lead in keeping fuel duty on hold. Putting it all together, the total cost to the exchequer will tick past £100 billion in the next fiscal year, according to the OBR.

Figure 1: Fuel duty forecasts over time

Source: HMRC

Throughout this period, ministers have stubbornly claimed that the timing is not yet right to unfreeze or raise rates. In 2012, defending his fourth freeze in two years, George Osborne said “Rising global prices have increased the cost of living for families here in Britain.” Ten years later, then chancellor Rishi Sunak defended his party’s seventeenth fuel duty freeze amid a similar cost of living crisis, saying his plan “will help people and businesses deal with rising costs.”

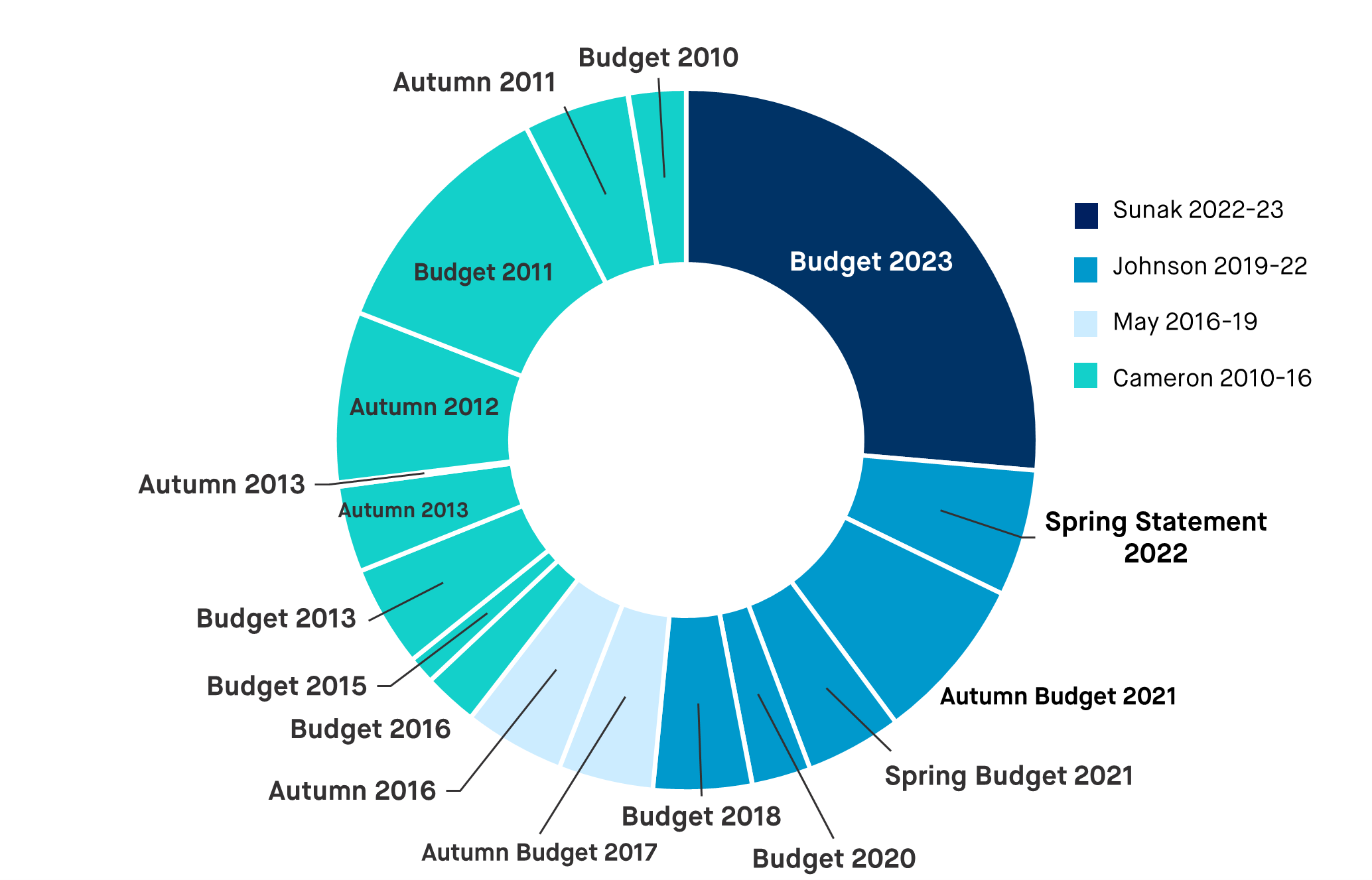

Figure 2: Annual losses by Budget

Source: OBR

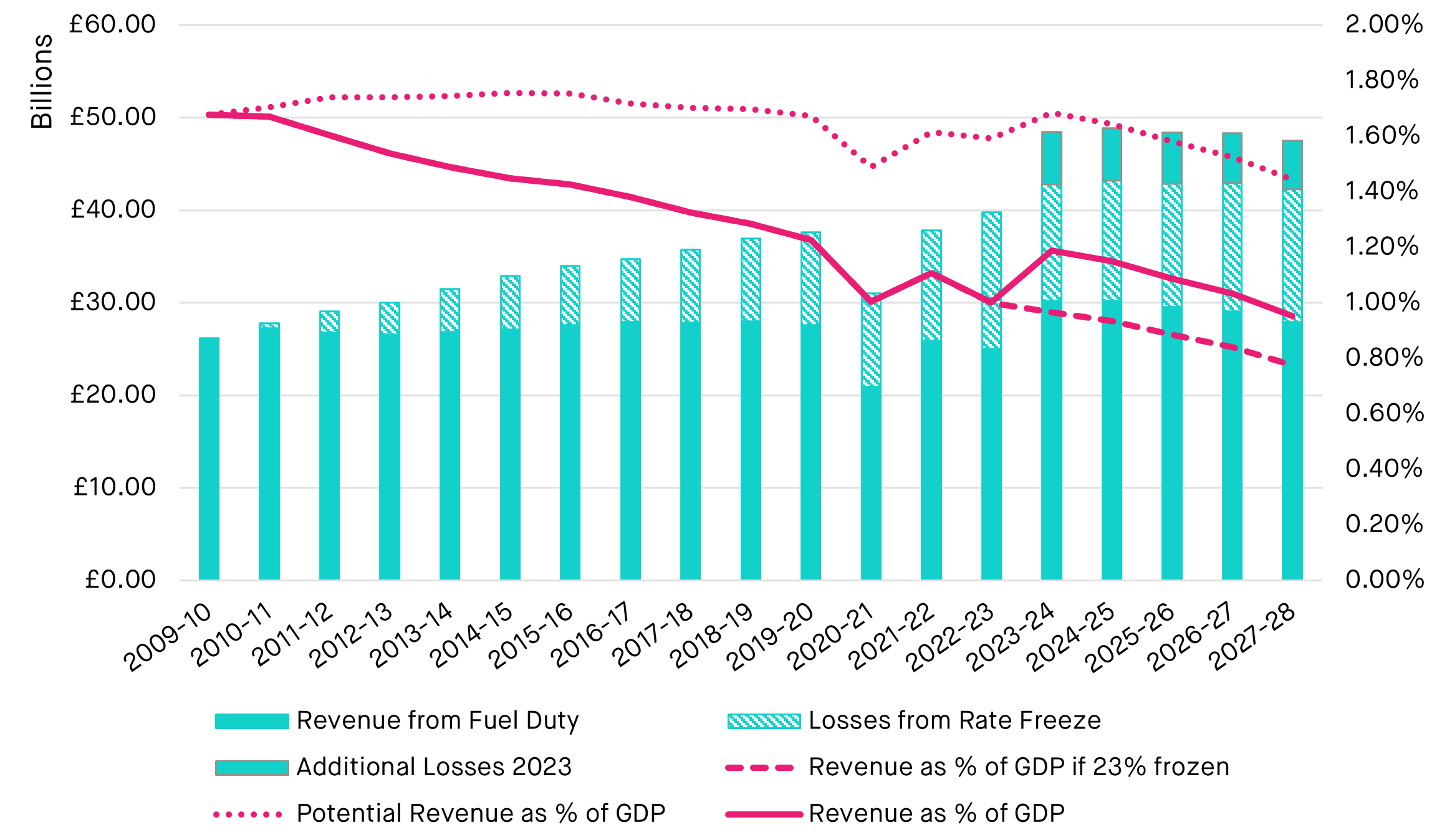

In 1999 the revenue generated for the public purse from fuel duty amounted to more than 2% of GDP. This was likely to fall to around 1.5% anyway, due to improvements in fuel efficiency and the growth of electric vehicles (that do not pay fuel duty). But today that figure is closer to 1%.

Current approaches risk further collapse in that revenue. In March 2022, then chancellor Rishi Sunak proposed a limited 12-month relief from fuel duty to assist households with rising costs. These temporary measures centred on a 5p-per-litre reduction in fuel duty, from £57.95p to £52.95p in unleaded petrol. There was also confirmation that this nominal rate would continue to be protected from inflation. That 12-month reduction alone cost the exchequer £2.4 billion, a figure that should be considered in the context of the ‘fiscal black hole’ that came to dominate political debate just six months later.

But now both senior Labour and Conservative figures are discussing permanently enshrining that temporary cut, despite their commitments to fiscal credibility. For Labour, Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves has called for a nominal freeze in fuel duty in the Budget on March 15th. Hunt is playing his cards closer to his chest, but a friend of the Chancellor briefed the Times that he is minded to maintain the freeze: “He gets that it’s a strong precedent to follow, albeit bloody expensive”.

Figure 3: Annual losses resulting from fuel duty freezes

Source: OBR

When Sunak announced the twelve-month reduction in price he suggested that these were temporary measures and a result of high wholesale oil prices resulting from the war in Ukraine. Thankfully, unleaded petrol peaked £191.55p-per-litre in July 2022 and has been falling since, as has diesel. As of January 2023, the price for petrol had fallen over 25% and now sits at £148.79p. This is not to say motorists are not struggling with high fuel prices, but wholesale outlooks have eased significantly since the Spring of 2022 and there are today better ways to help motorists than through another unfunded cut.

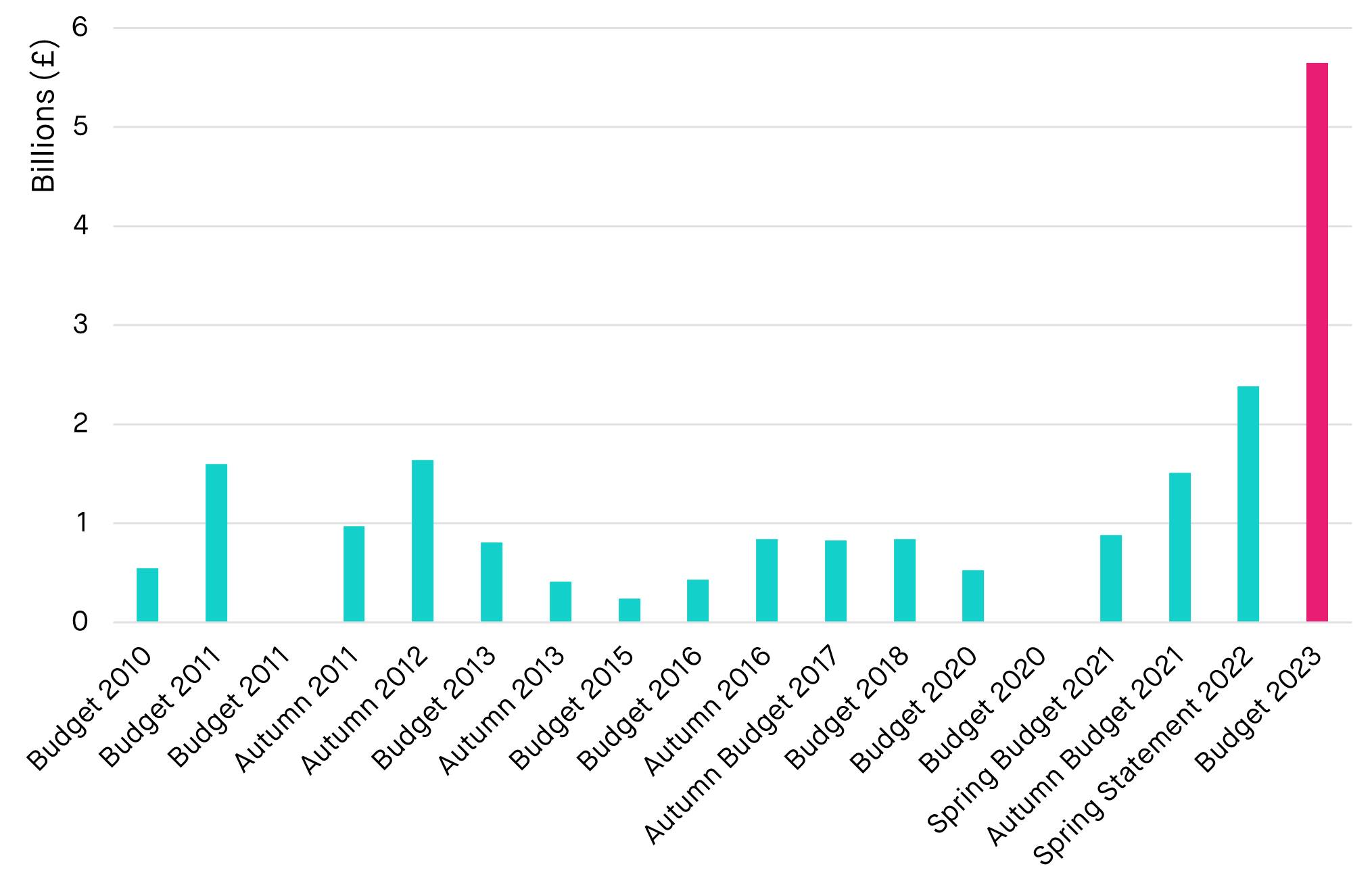

Accounting for inflation, making the 2022 reductions permanent would cut future fuel duty revenues by 23% and cost government £5.5bn annually over the next five years. Many observers have become blasé about fuel duty cuts, treating them as routine and unremarkable. But this would be the biggest duty cut in history. When measuring losses during the first year of implementation, this cut is double Sunak’s 2022 reduction, which itself set a record, and more than triple George Osborne’s 2011 1p cut. To put it in perspective, embedding those fuel duty cuts would require the allocation of more public money than the entire levelling-up fund every single year. A fuel duty freeze in the March Budget would cost more than £27 billion over the next five years, and much more over the medium term. While proponents claim this years’ £5.5 billion could be funded by savings from the budget for the energy price guarantee due to unexpectedly low energy costs, the remaining £21.8 billion remains unaccounted for.

Figure 4: Cost of fuel duty freeze/cut in the first year post-implementation

Source: OBR

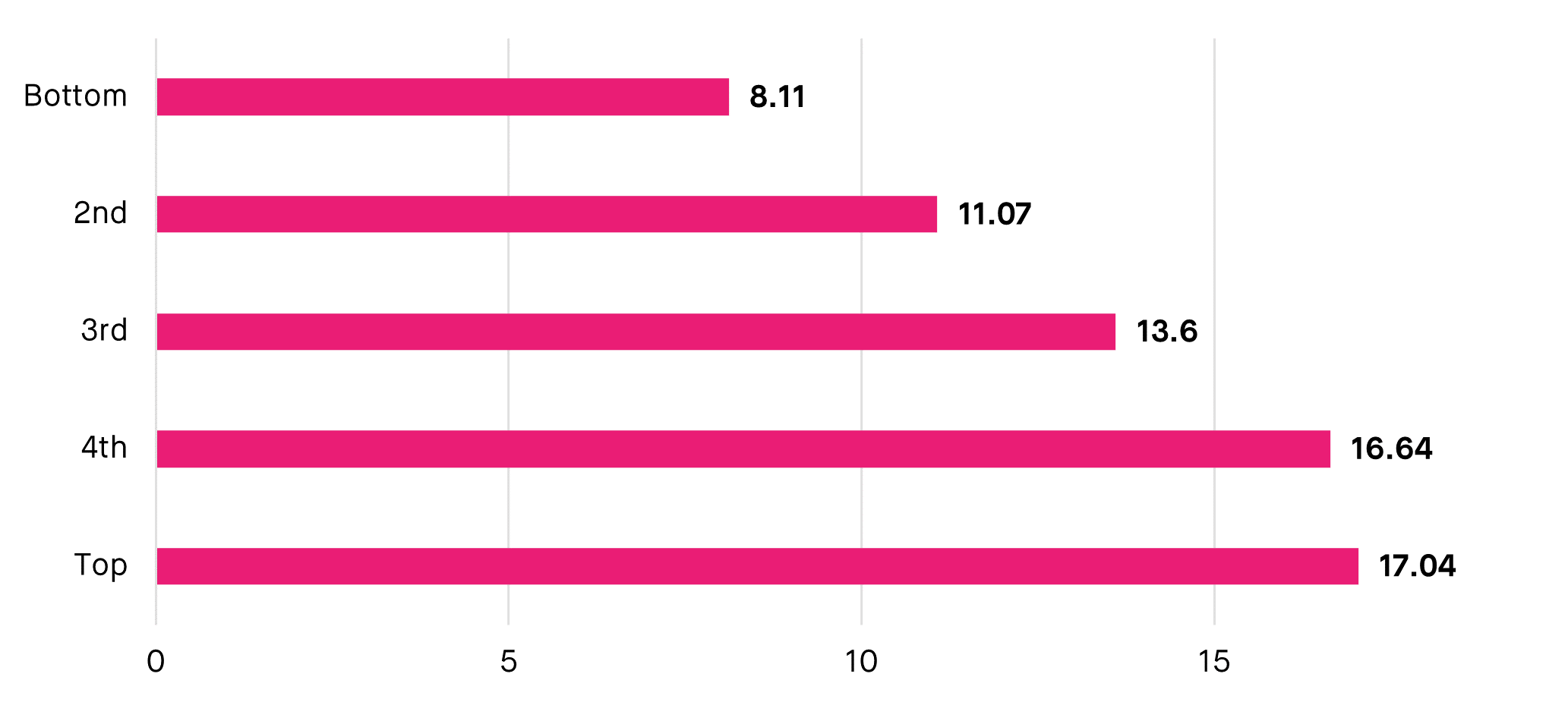

Fuel duty’s critics often cite its impact on poorer motorists as a rallying cry, claiming that it is a tax on poor drivers. In fact, the burden of fuel duty falls more heavily on the better off, meaning they are the biggest beneficiaries of cuts – £17 billion of the fuel duty cuts and freezes between 2010 and 2020 went to the richest households, more than double the £8 billion that went to the poorest.

Figure 5: Total accumulated savings (£ billions) by income quintile, up to 2020

Source: ONS

Since coming to power, Sunak and Hunt have promised to prioritised fiscal responsibility, and argued for the necessity of painful tax rises and cuts to public services. Against a backdrop of public sector strikes and bleak headlines about the public finances, the Chancellor is signalling that he has no money to spare either for public sector pay or the income tax cuts being demanded by some of his Conservative colleagues. “With volatile markets and high inflation, sound money must come first,” the Chancellor said in a Bloomberg speech on 27th January. But at the same time, Hunt looks set to sign off on unfunded tax cuts worth over £20 billion.

Meanwhile, continued fuel duty freezes risk damaging the UK’s net zero ambitions and undermining UK claims over green industry. The freeze in fuel duty since 2010 increased the UK’s CO2 emissions by as much as 5%, according to Carbon Brief. This is largely due to increased road transport emissions, which were expected to fall 13.3% by 2019 yet instead grew 2.6%. David Begg and Claire Haigh have estimated that between 2011 and 2018 freezes caused an additional 4.5 million tonnes of CO2, along with up to 60 million fewer rail journeys and 200 million fewer bus journeys, while traffic grew 4%. The Local Government Association reports that in the same period, over 2,000 bus networks outside London had been rescaled as a result of budget cuts. Last year’s cancellation of preferential VED treatment will add to this output, which made EVs more expensive relative to traditional vehicles by applying the same rate of sales tax to both. The environment has been identified as a key strategic weakness for Conservatives attempting to woo voters from other parties. Labour meanwhile looks to use this issue as a vote-winner in 2024. Both parties must now consider how to explain to environmentally-interested voters why British car emissions will remain high over the next ten years.

Fuel duty was never meant to disincentivise travel. The revenue it generated was intended to motivate more efficient decision making on transport options and fund better public transit across the UK. The £27 billion raised from fuel duty over the next five years could fund a significant stimulus for public transport in areas forced into expensive car ownership due to a lack of alternatives. It could go towards new buses and rail hubs that would improve accessibility for rural communities and better connect isolated areas. Concessionary bus fares in rural areas could be reintroduced after they were cut for austerity. That money might be diverted towards EVs by reinstating the plug-in grant for M1 vehicles, extending the eligibility for electric vehicle charge-point grant, or subsidising EV conversions.

Alternatively, that £27 billion could be carelessly thrown into the bank accounts of the better-off, doing nothing to give Britain a more sustainable transport system and quite likely delivering no great political benefit to its authors. Previous fuel duty cuts have been fiscally expensive but electorally insignificant, since voters appear to take their savings for granted – if they notice them at all.

And all of this, remember, subject to a consensus between two main parties who say they are committed to both net zero and fiscal responsibility. When it comes to sound money and sensible transport policies, voters looking to either of those parties for leadership might well be disappointed.