Many of those who support fuel duty cuts say they are justified because they give financial help to people who can barely make ends meet. In fact, as Gideon Salutin shows, fuel duty is mostly paid by the better off, meaning cutting it is little more than a tax cut for the rich, often funded by cutting services that are used by the poor.

When David Cameron defended the first fuel duty cuts in 2010, he claimed they would be “helping hard-pressed consumers.” He neglected to mention that the poorest fifth of society, though hard-pressed, would receive less than 10% of these savings, while the richest would receive 32%. The same story is set to play out again in the coming Budget.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt is rumoured to be mulling yet another cut to fuel duty revenues by including provisions to make permanent Sunak’s temporary 5p cut and freeze. Last year, Sunak’s cut cost the Exchequer £2.4 billion. Of this just £109 million (4.6%) is estimated to have reached the poorest decile. Making the cut permanent would decrease forecast revenue by 23%, and cost the Exchequer £27 billion over five years in unfunded tax cuts. Of the lost revenue, £8.5 billion (27.1%) would likely go to the richest fifth in society.

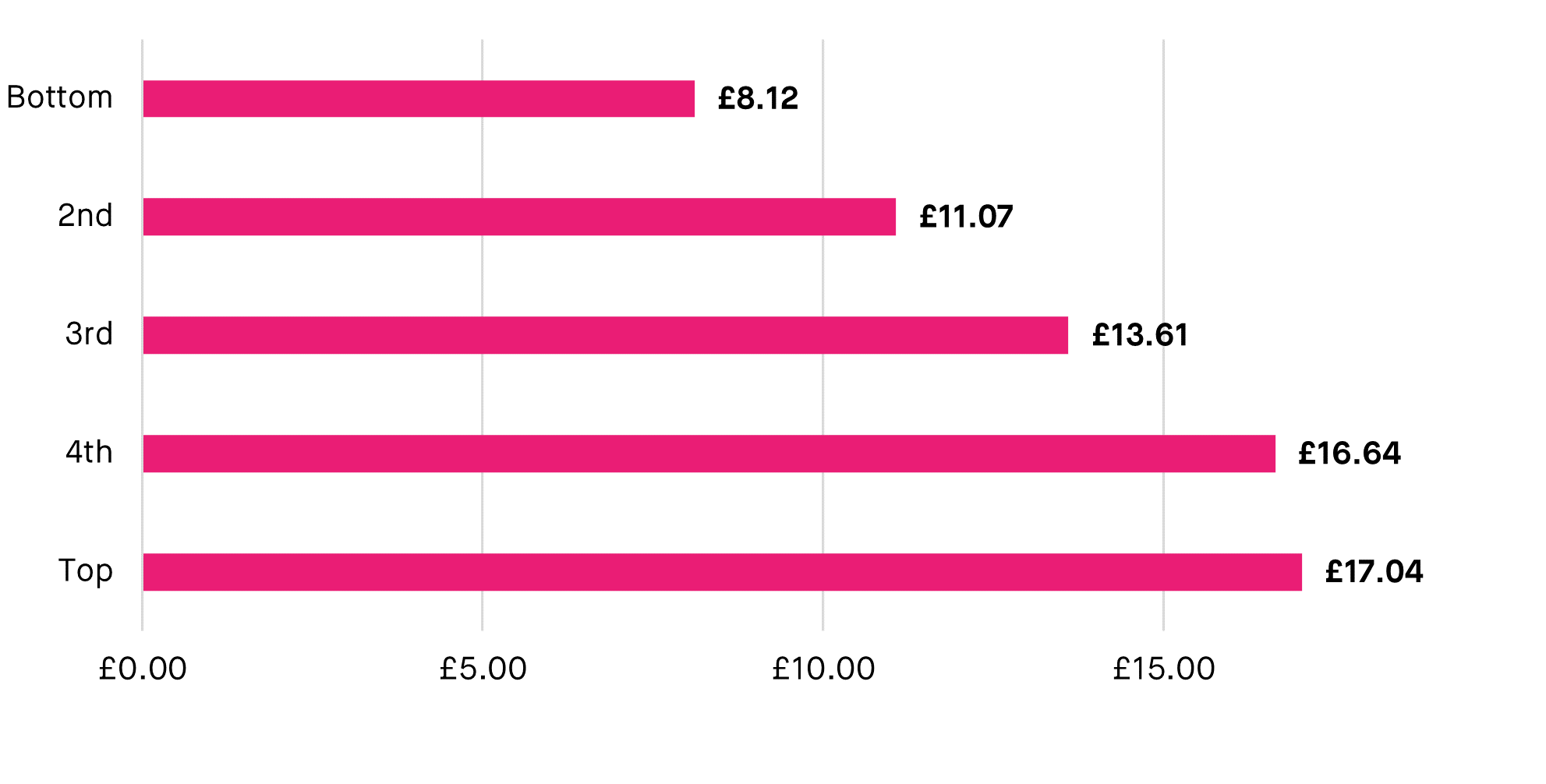

Since 2010, fuel duty cuts and freezes have benefitted the top quintile of earners twice as much as the bottom 20%. The wealthiest people in the UK saved £17 billion through fuel duty freezes, compared to just £8 billion which went to the poorest. In the popular imagination, petrol and diesel taxes are a heavy burden on struggling families. In reality, 38% of the poorest quintile of households in the UK have no car available, while it is the richest that are more likely to splurge on gas-guzzling SUVs and second (or third) vehicles.

Figure 1: Total accumulated savings (billions) by quintile up to 2021

Source: ONS

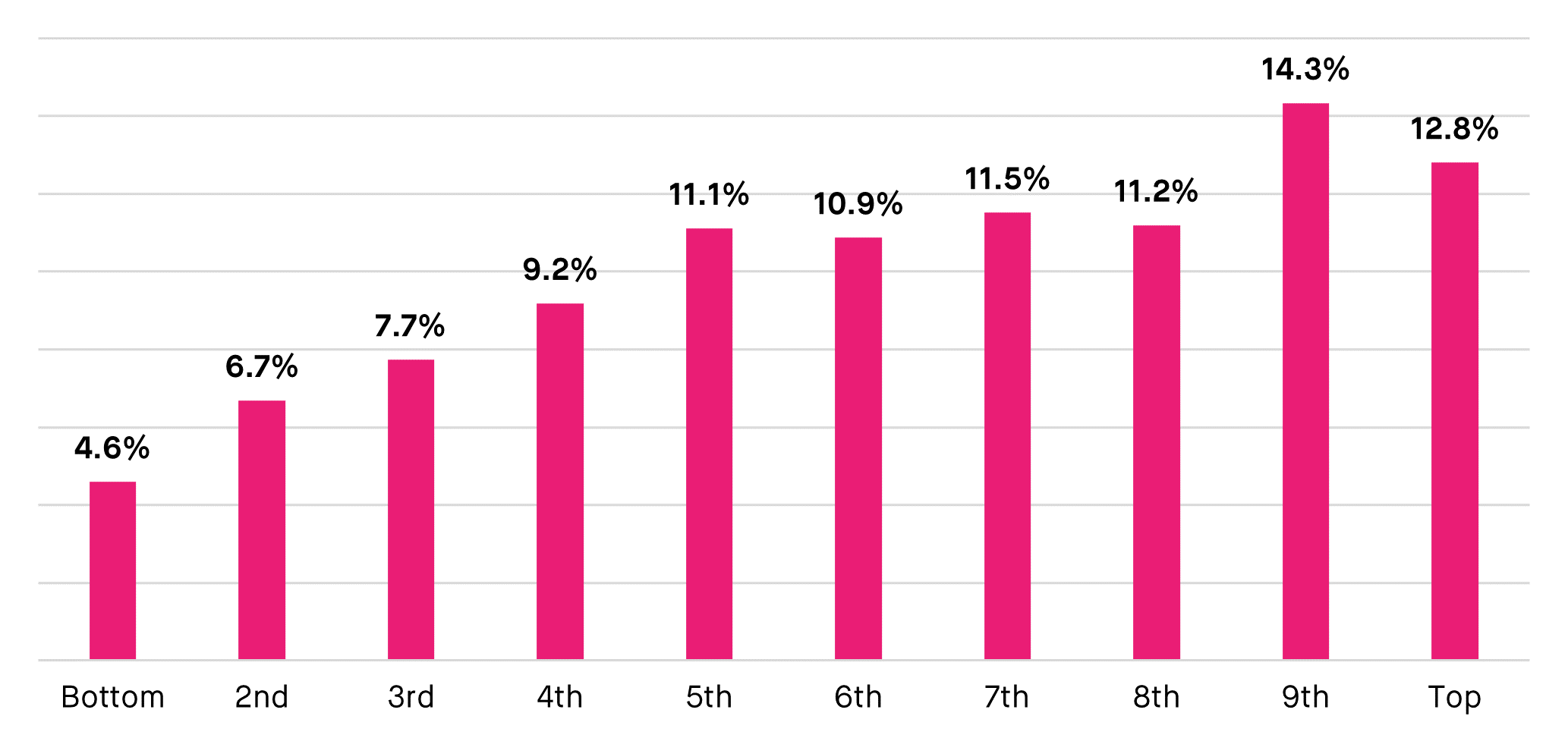

If the Chancellor were to go ahead with a duty freeze, the bottom decile would receive just 4.6% of savings from an upcoming fuel duty freeze compared to 12.8% for the top 10%. This is based on 2019 expenditure and does not account for changes in behaviour prompted by price decreases. Altogether, due to their lower expenditure on fuel, the bottom 50% will receive just 39% of total savings.

Figure 2: Share of savings from potential fuel duty freeze by decile

Source: ONS

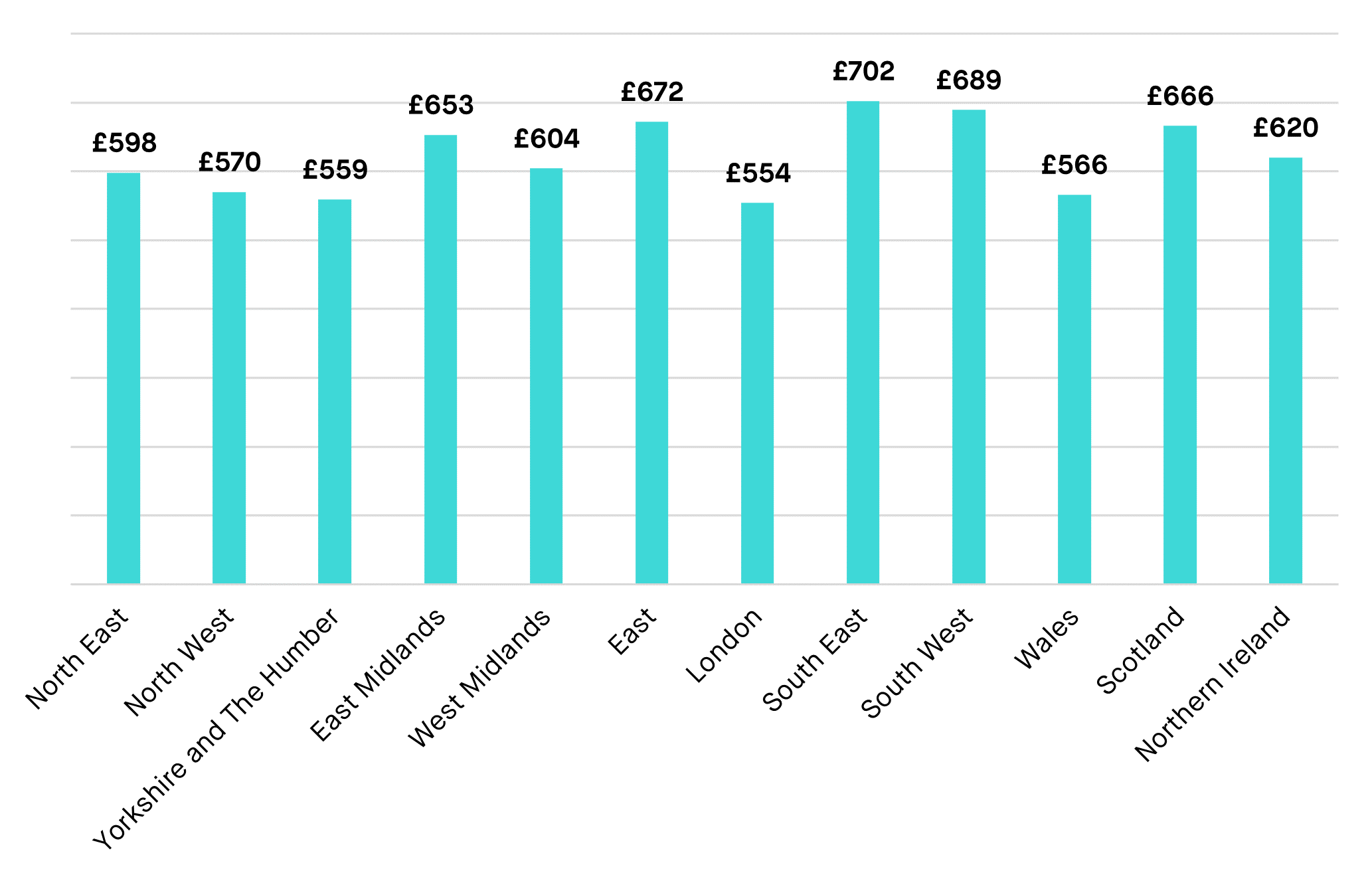

Due to higher rates of driving and their propensity to own multiple cars, residents in the South East would benefit more than any region in the UK. 2021 data shows that Southerners currently average more spending on fuel duty than any region in the UK, with the South East at £702 and South West at £689. Comparatively, Britain’s most disadvantaged regions spend little, with the North East at £598, North West at £570, and Yorkshire and the Humber at £559. Any freeze will therefore send more savings to the UK’s most advantaged regions than it does to the North. Despite endorsements from both major parties, another fuel duty freeze will send more of Britain’s money to its richest at a time when it is desperately needed to fund services across the country.

Figure 3: Average per person fuel duty payments by region

Source: ONS

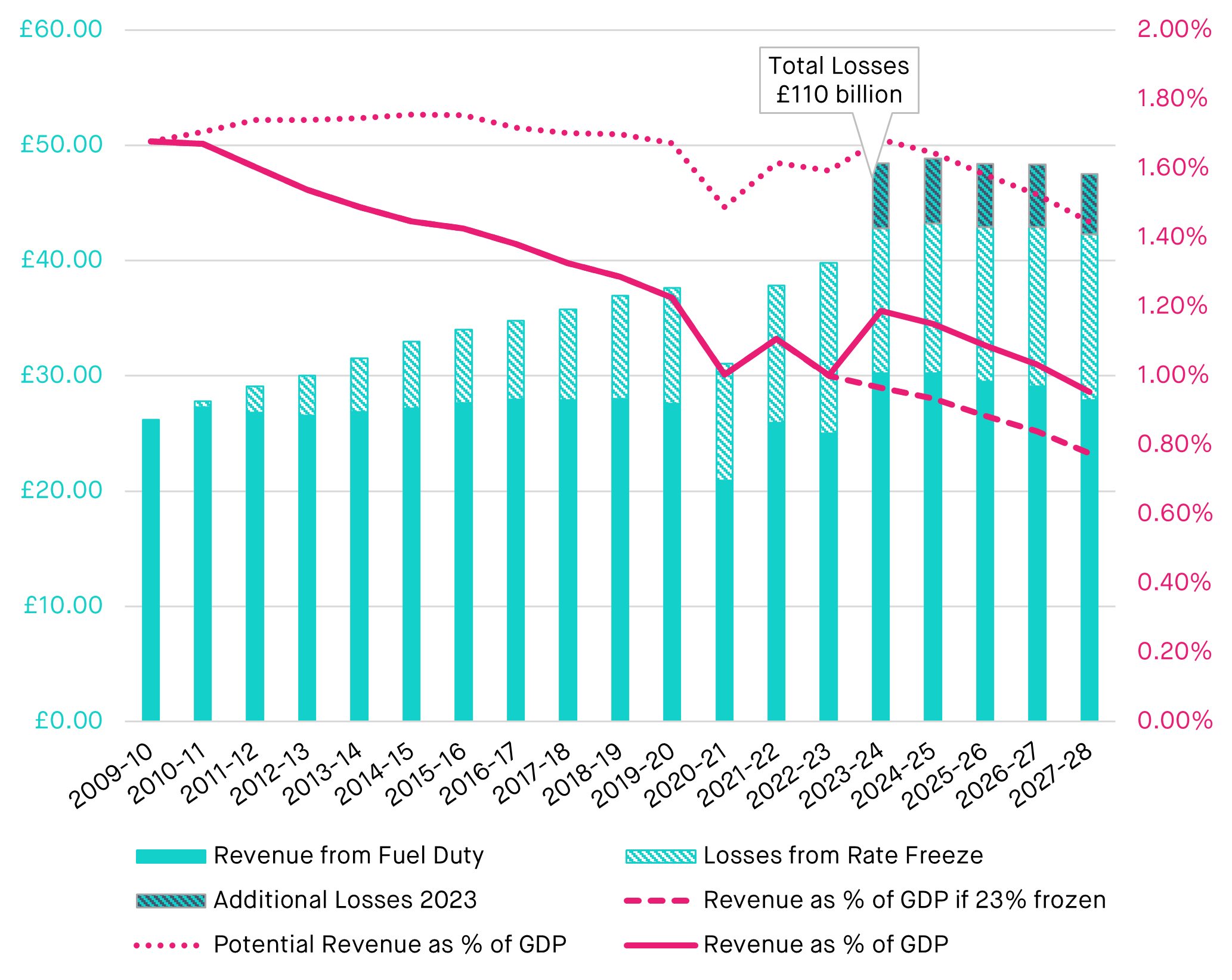

This year, total losses to the public purse will hit £100 billion, and will explode over the next few years to reach £188 billion by 2028. These losses have accumulated during a period of austerity in which public services that primarily benefit the poor have been cut.

Figure 4: Annual losses (billions) resulting from fuel duty freezes

Source: OBR

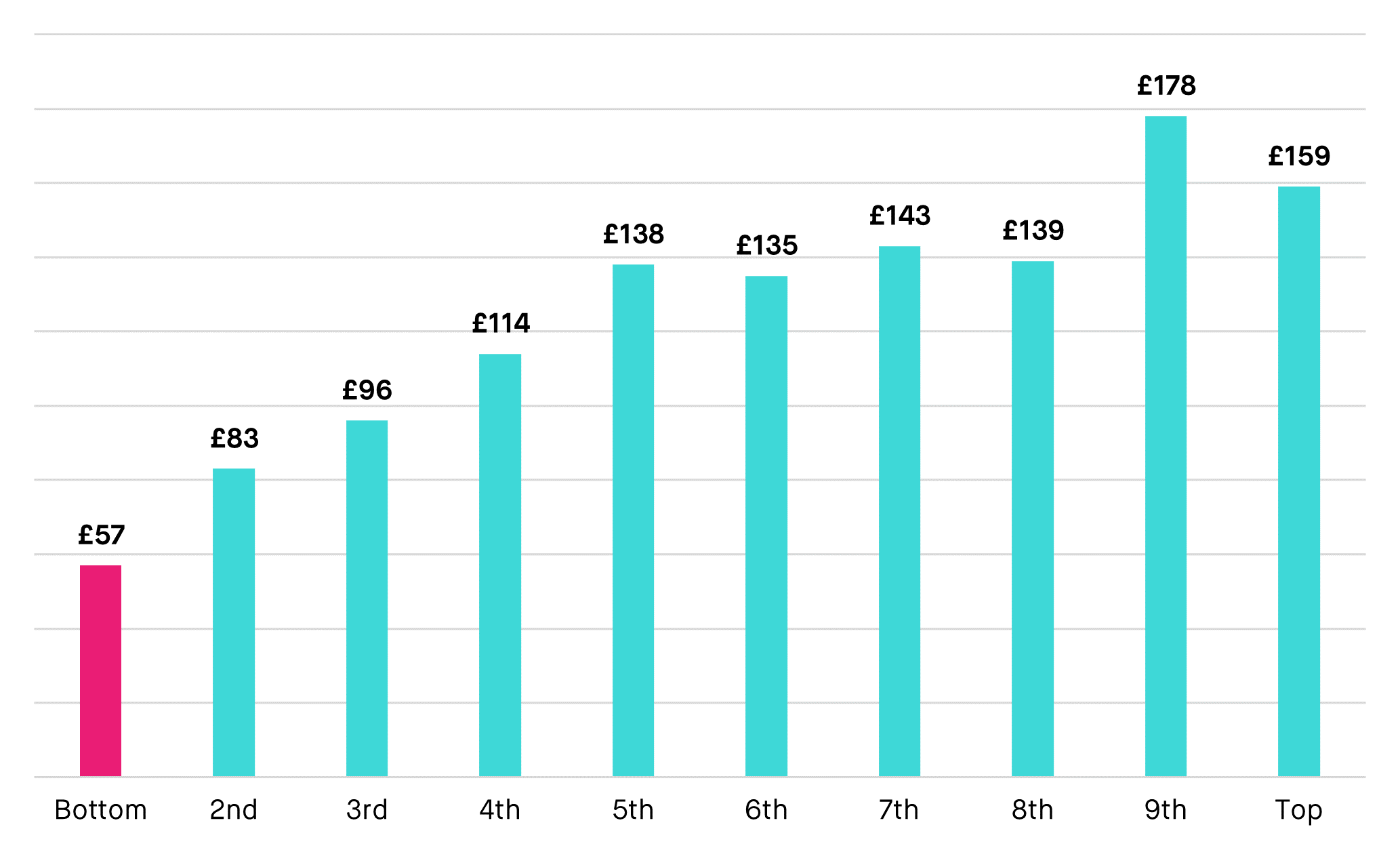

Despite the claims of campaigners who portray fuel duty cuts as help for people who are struggling, people in poorer deciles gain relatively little from these freezes, and much less than richer people. An average household in the lowest income decile is estimated to have spent just £232 on fuel duty in 2019, the most recent year with regular travel patterns. This translates to £4.46 a week. Any cuts in fuel duty will therefore be barely noticeable to many motorists, even poorer ones, while having significant impacts on the public finances.

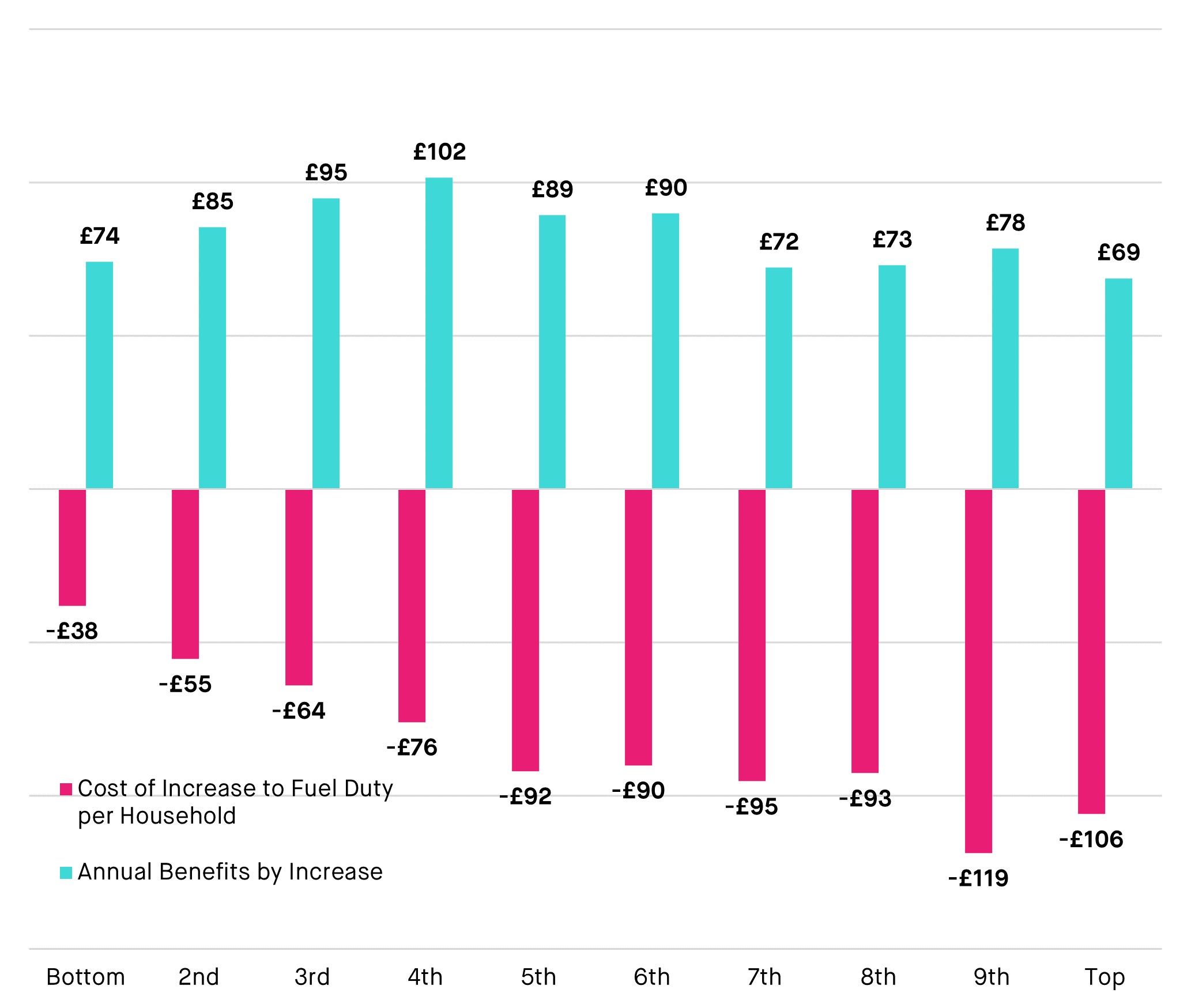

In reality, poor households stand to gain more than they lose on fuel duty. If Jeremy Hunt were to go ahead with the 23% planned increase in fuel duty, this would cost households in the lowest decile £38 per year. Yet if that government revenue were reinvested in public spending – following the same overall mix of benefits and public services – the poorest households would get almost twice as much back, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 5: Annual effect of 23% fuel duty increase on household disposable income, by decile

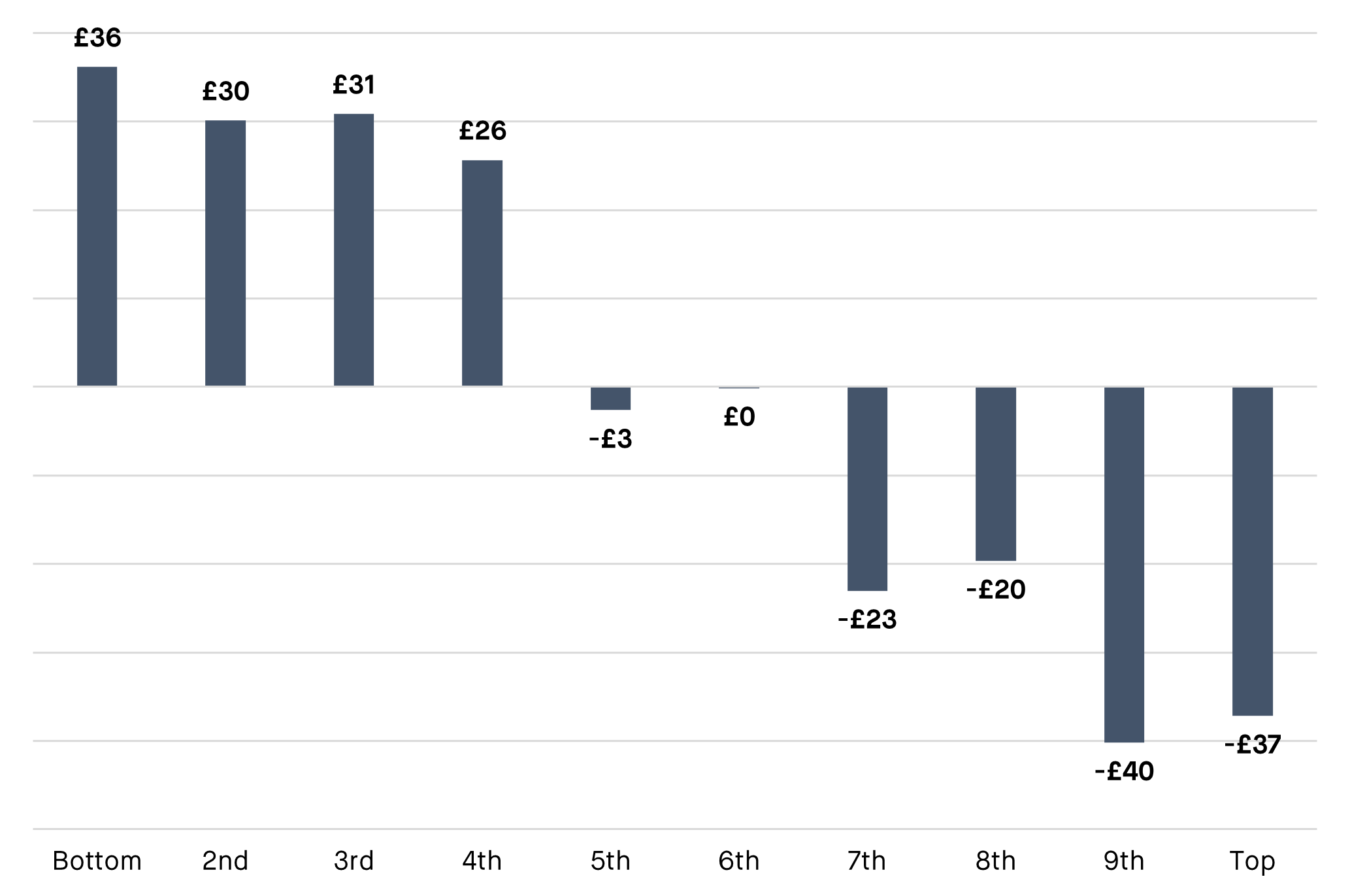

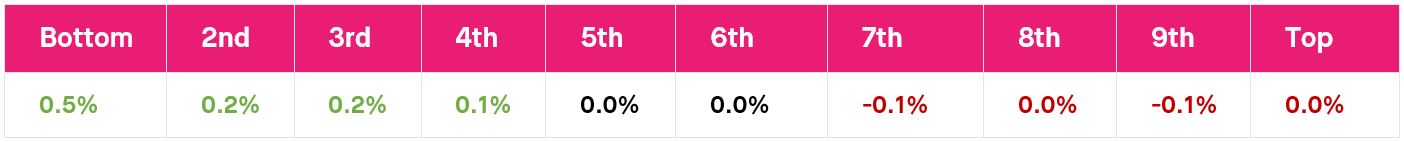

The net effect of increased fuel duty recycled to public spending (in Figure 4) would be that households in the bottom 40% would receive an annual net gain from fuel duty averaging £31, funded by losses of up to £40 in richer deciles. As a percentage of after-tax income, the fuel duty increase would give the greatest benefit to the poorest decile, who would gain 0.5% on their annual income. Those in the top 50% would lose less than 0.1% of their annual income.

Figure 6: Net effect of 23% increase in fuel duty’s, by household income decile

Table 1: Net Effect as a Share of Post Tax Income, by decile

This is not to claim no motorists are struggling. When viewed as a share of disposable income, fuel duty cuts can appear progressive, because the poor see a greater percentage change in their take-home income. But this misunderstands the significant effects cuts in fuel duty have on public expenditure. When it cuts duty, government also cuts service funding, giving with one hand and taking with the other. Without a cut, revenue from fuel duty can be spent where it is needed. Alternatively, a great deal can be pocketed by those who need it least.

Figure 7: Annual fuel duty expenditure by decile (2019)

Source: ONS

If the government actually wants to do something to help the most vulnerable, public transport could be a start. One Oxford study revealed that the poorest 5% make 113 bus trips a year, while the richest 5% make just 31. 30% of the poorest quintile of adults live in households without a car, and this rises to two-thirds among job seekers. With services on their knees, a stable revenue stream could be used to expand rail hubs, provide loans for electric vehicle purchases, and spur economic development in disadvantaged communities. Over the past ten years, bus networks have been sharply reduced, with thousands of routes abandoned which has increased isolation in remote communities. Last year, almost 10% of bus networks in the UK were cut. Note that this is just an average, and some towns have lost entire bus access. The revenue recovered from fuel duty could be spent reconnecting these communities, increasing access for those without cars, and providing greener transport options for those who do.

While fuel duty is hardly unpopular, the Government should trust the public to recognise that coddling richer motorists comes with costs too. According to a Department for Transport public opinion survey in 2020, 77% of respondents supported reducing road traffic in England’s towns and cities. Another 86% supported improving air quality while 83% supported reducing traffic congestion.

Instead of indulging in a shallow and misleading approach to fuel duty, both major parties should take the opportunity of next month’s Budget to have a mature debate about the costs of subsidising car use, and the impact that has on both the environment and social inequality.

Those who want fuel duty cuts to support people who are financially struggling are acting in good faith, seeking changes they think will offer that help. But despite their honourable intentions, fuel duty cuts are in reality a really bad way to get help to ‘White Van Man and Woman’ and other hard-working Britons.