The latest figures show that the Immigration Skills Charge (ISC) has raised almost £1.5 billion in revenue since its introduction. In this blog, Jonathan Thomas argues that the government should be clear that it is devoting these funds towards the ISC’s stated aim of addressing skills gaps in the UK workforce, rather than allowing them to disappear into an all-purpose black hole.

The Context

The ISC was introduced from April 2017 by the 2016 Immigration Act. The ISC is a per worker charge which must be paid by employers sponsoring skilled foreign workers into the UK for more than a six-month period under the UK’s employer sponsorship system.

The Explanatory Memorandum accompanying the introduction of the legislative change to effect the ISC stated that it was being brought in:

“to incentivise employers to invest in training and upskilling the resident workforce, thus reducing reliance on migrant workers … [and] … to increase UK productivity … The income raised by the charge will be put towards addressing skills gaps in the UK workforce.”

Certain exceptions to, and differential rates of, the charge apply, depending on the size of the sponsoring organisation. The amount that is paid also depends on the amount of time the worker is being sponsored for. The ‘normal’ rate (i.e. for medium/large sponsors) of the charge is £1,000 per year.

Brexit incidentally had a potentially significant impact on the scope of application of the ISC. This is because, when the UK was part of the EU free movement of workers system, workers coming into the UK under that system did not need to be sponsored, so were outside the scope of the ISC. But, with Brexit and the ending of EU free movement for work to the UK, the employer sponsorship system now encompasses both EU as well as non-EU workers. Thus, the potential scope of the ISC to support skills budgets is now in effect greatly increased.

As the purpose of the ISC is to address skills gaps in the UK workforce, while the charge is paid to the Home Office, it is not retained by it, remitted instead to HM Treasury as Consolidated Fund Extra Receipts. But the amount of the annual income from the ISC is still revealed in the ‘Statement of Revenue, Other Income and Expenditure’ in the Home Office annual report and accounts.

The Latest

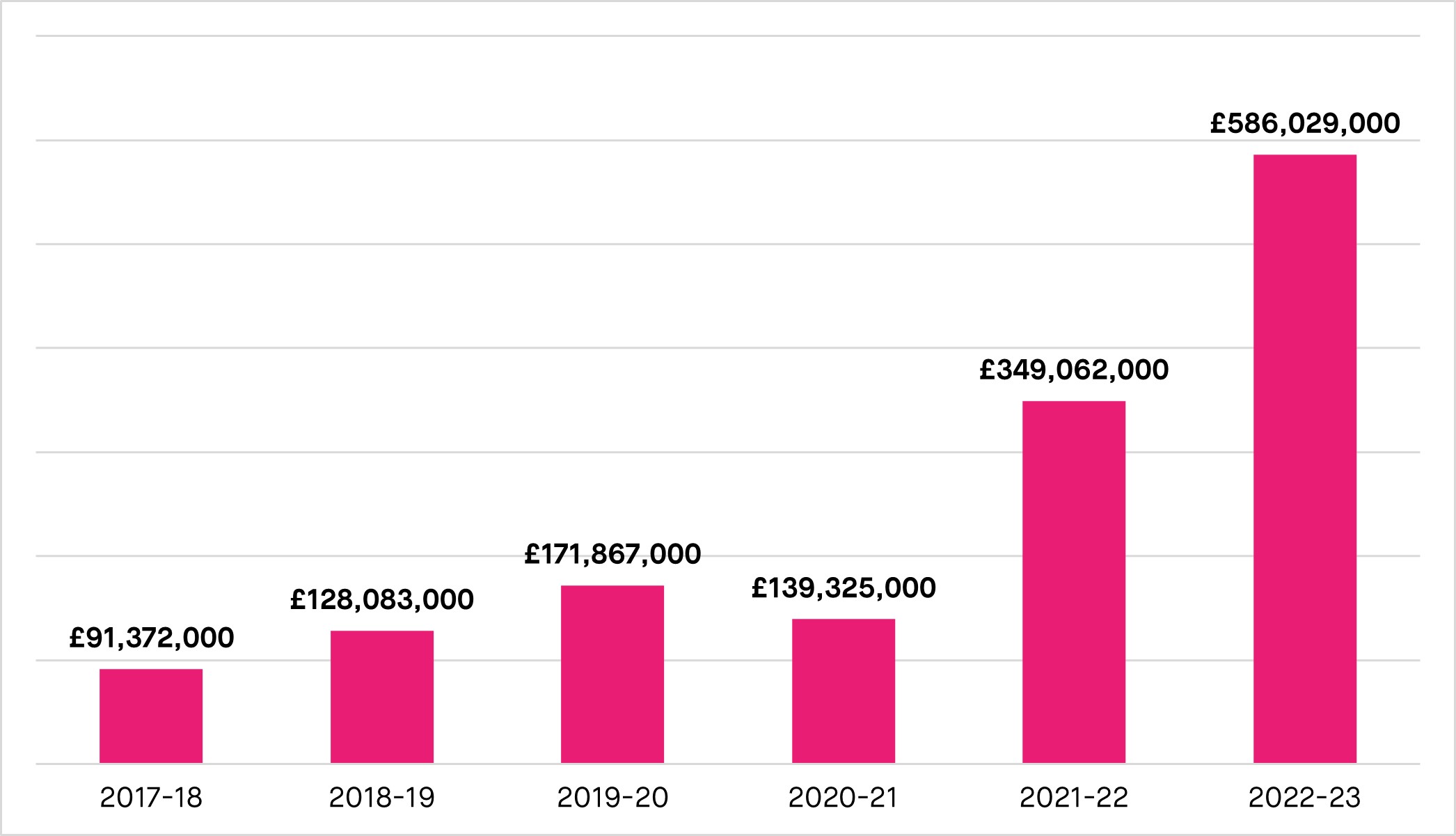

The latest figures, just revealed for the 2022-2023 period, show ISC receipts for the year ended 31 March 2023 of £586 million. The below chart shows the amounts and the trajectory of the proceeds generated by the ISC since its introduction.

Figure 1: Immigration Skills Charge – annual receipts 2017-2023

Source: Home Office annual reports and accounts

Notwithstanding the 2020-2021 drop caused by the pandemic, this leaves the cumulative income generated by the ISC to end of March 2023 standing at £1.47 billion.

Our Argument

As set out in our recent ‘Whole of the Moon’ report on UK labour immigration policy, we argue that:

- There has been a public perception – most recently fuelled by comments from senior politicians of both the two main political parties – that British business is self-serving and short-termist in its use of immigrant workers, under-investing in domestic skills, and using overseas workers to supplant rather than supplement domestic workers. In this framing, business is regarded as accruing all, and sharing none, of the gains of labour immigration.

- In theory, the ISC looks to be ideally placed to counter this framing, and a rare example of joined-up labour force planning – the proceeds of a charge paid by employers to hire each sponsored foreign worker today are to be used to fund the training of the local workforce of tomorrow.

- In practice though, the outcome of the ISC does not appear so joined-up. There is zero transparency or accountability for how the proceeds of the ISC are applied and used; they seem to disappear into a general all-purpose blackhole.

- In terms of the ISC, the government should ‘use it or lose it’; that is, if the ISC is going to continue to be levied on businesses sponsoring overseas workers, the proceeds of the ISC should be used for their intended purpose – tangibly invested into developing the domestic skills base – and transparently so, with publicity given to this fact.

- The potential positive power of the ISC should be viewed as operating on two levels. Not only on the practical level; that is, the actual investment in skills and training which the proceeds of the ISC can fund. But, as importantly, also on a symbolic level; sending out an important and well-publicised message, that:

- the government has required employers to pay the ISC whenever they sponsor an overseas worker, and

- this charge is then being used directly to fund investment in the domestic skills base.

- In this way, the ISC can be highlighted as a clear, structured mechanism through which:

- the gains that businesses are viewed as having received from their access to and use of labour immigration are shared; and

- reinvested in those who do not see themselves as so far having benefited from those gains, bolstering not only public outcomes, but also public support for labour immigration on a more balanced basis.

This would be good not just for workers and for business, but also for government – indeed, for any actor with an interest in ensuring that the workings of labour immigration system are properly and more strongly rooted in public consent.