The long-awaited ban on no-fault evictions continues to evade us, based on claims that it will harm the rental market and reduce supply. But what does the evidence say? Looking at Scotland and other jurisdictions suggests that claims of harm are entirely misplaced.

Yesterday, the King’s Speech confirmed that the Renters Reform Bill will go ahead, but it appears its headline policy will be left behind, after Michael Gove delayed plans to ban no-fault evictions in the private rented sector following faulty economic claims that it would damage the rental market.

The change would have banned landlords from evicting tenants without cause. Currently, under Section 21 of the 1988 Housing Act, private landlords can repossess their properties from assured shorthold tenants without needing to establish any faults, such as unpaid rent or property damage. These are the most popular method used by landlords to evict tenants, and campaigners including Shelter UK and Citizens Advice have argued banning the practice would level the playing field between tenants and landlords. Shelter Scotland explained “Ending no-fault eviction in the PRS removes the possibility of a retaliatory or revenge eviction, and so gives tenants the power to act as strong consumers.”

But the ban, originally proposed in the Conservative 2019 Manifesto, was withdrawn from the bill as 30 to 80 MPs threatened to vote against it. They argued the ban would cause landlords to exit the market, shrinking the properties available to rent at a time of high demand. As one MP explained: “The consequences of this well-meaning legislation is a reduction in supply as landlords continue to leave the market. Where will these tenants go at a time of huge demand? This is an inflationary measure that will make things worse for tenants.” His fears are echoed by other Tory MPs, as many as eighty of whom threatened a vote to maintain Section 21. Since this threat, Gove has delayed any ban indefinitely until “sufficient progress” has been made to reform court processes.

But their claims don’t hold up to evidence.

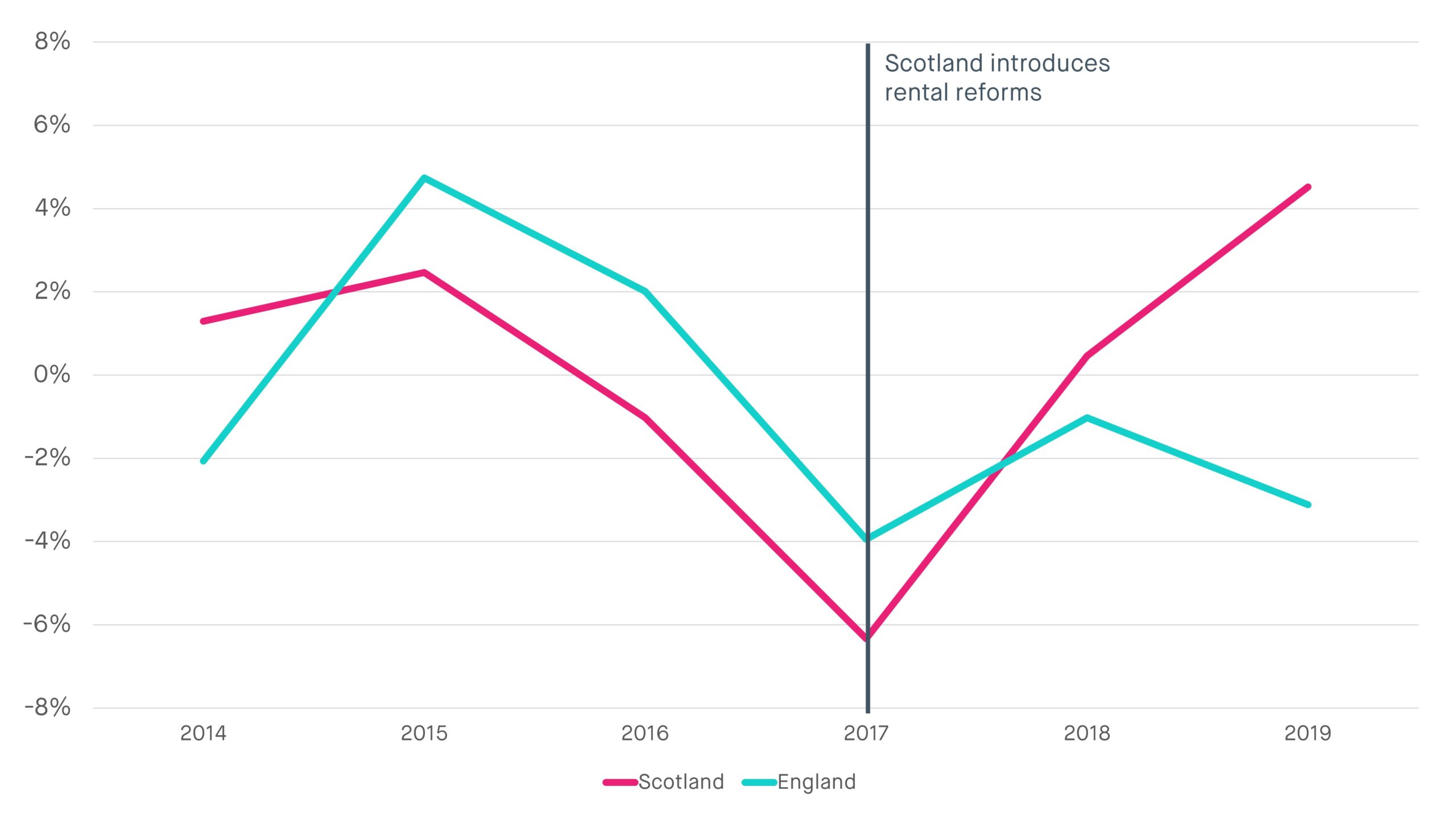

In Scotland, no-fault evictions were effectively banned in December 2017, yet concerns that the private rented sector would shrink proved pessimistic. Its private sector grew at a faster rate between March 2018 and March 2020 than England’s, though the two had followed similar trends up to that point. In 2019, Scotland saw its private rented sector grow at its fastest rate since 2011.

Figure 1: Percentage increase in the share of households which are rented privately

Source: Scottish Household Survey and English Housing Survey

This is especially striking given that Scotland’s ban was accompanied by wider protections for renters. These included introducing open-ended tenancies, limiting the frequency of rent increases, a new public officer capable of restricting rent increases if they consider them unreasonable, demanding longer notices on behalf of landlords to vacate, and the potential for local caps on rent increases. In comparison to Gove’s plan, these changes made renting far more burdensome for landlords, yet were followed by market expansion.

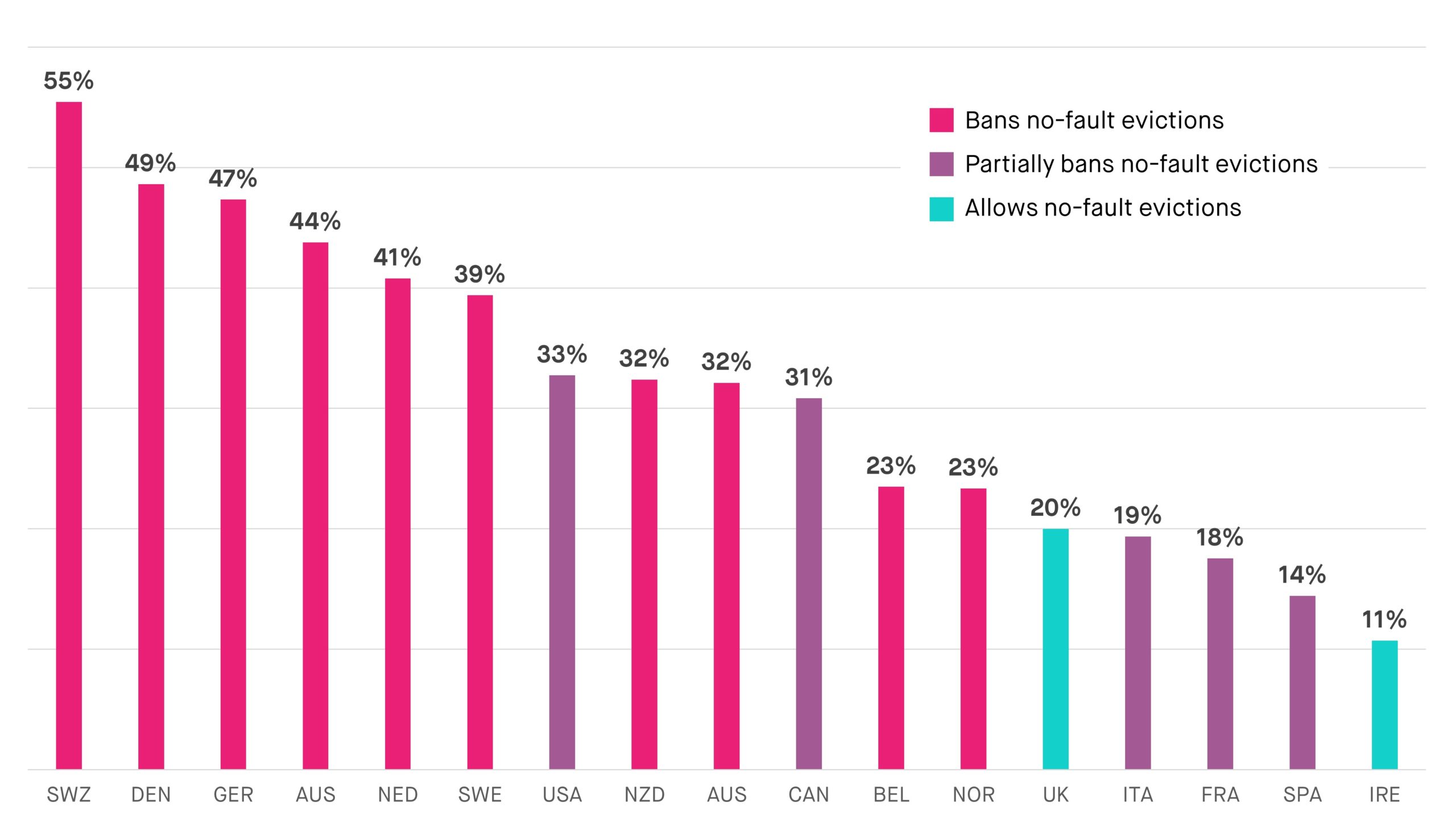

The claim also does not hold up to international evidence. In comparable European and Anglosphere economies, countries that have banned no-fault evictions tend to have a larger private rented sector. Switzerland, Denmark, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Sweden, New Zealand, Australia, Belgium, and Norway all ban no-fault evictions while seeing a higher proportion of their populace renting from private landlords. The only outliers to that list include partial bans. Some US states (such as California) and Canadian provinces (such as Quebec) ban the practice, and see a higher proportion of their population in the private rented sector than the UK. On the other hand, Italy, France and Spain allow for no fault evictions in specified circumstances, such as when the landlord moves into the property, and have smaller private rented sector. Ireland is the only other large European economy that allows no-fault evictions, and has the lowest proportion of the population renting.

Figure 2: Share of households in the private rented sector by country and eviction regulations

Source: OECD Housing Market Database

Of course, causality may flow the other way – countries with larger rental sectors may be more likely to regulate them. There may be a feedback loop involved: as a country gets more renters, their voice grows stronger allowing them to lobby for greater protections which further increase demand. But these cross-national comparisons highlight the fact that England is an outlier, and that other countries manage not just well functioning, but larger, thriving private rented sectors without no fault evictions.

What we’re seeing goes against the claims that bans on no-fault evictions limit the role of the rented sector. Rather than decrease its size, it is possible banning the practice leads tenants to feel more confident when renting, increasing demand and taking pressure off the homeownership market. At the same time, tenants would be better protected, and more willing to voice complaints about abusive or inefficient landlords who might otherwise retaliate.