In the face of budget cuts of around 50% from central government since 2010, some of England's councils have been very enterprising.

The Public Works Loan Board is an arm of HM Treasury which provides investment loans to local authorities at subsidised rates with virtually no accountability. Councils are increasingly using these loans to invest in commercial property.[1] For instance, a property is leased from its owner and renovated into a shopping centre which attracts commercial tenants. The rental payments are used to pay the owner for the lease and the interest on the initial loan. Whatever is left can go towards filling gaps in the council’s budget. Some councils have bought properties outright and built up significant property portfolios. Spelthorne Borough Council covers a population of around 95,000 people. It manages a financed property portfolio of more than £1 billion.[2]

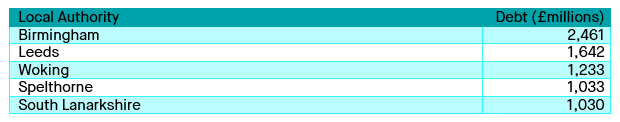

Figure 1: Local Authorities by Outstanding Debt to the Public Works Loan Board, excluding TfL and GLA

Source: MHCLG Borrowing and Investment Live Tables Q2 2019-20[3]

Is this model sustainable? In the event of an economic downturn and further challenge to high street retailers, will shops struggle to pay rent or close down entirely? What would happen in this situation? Not only would the council be indebted to the owner of the property, they would also be indebted to central government. Practically, the proprietor expects the council, as a government entity, cannot go bust. This then raises the question of what would happen if a council cannot repay its debt to Treasury. Could more councils follow in the path of Northamptonshire County Council, which became insolvent last year?

These developments have not gone unnoticed in central government. The National Audit Office is currently investigating commercial property investment by councils and is due to publish its findings early next year.[4] The Treasury took the unusual step of suddenly raising the interest rate on PWLB loans in October without warning.[5] The dilemma for Treasury is that raising this rate may have further unintended consequences, especially for councils which are using loans for genuine investment.

Even though there is some political agreement that austerity is over, there is little prospect of a sudden injection of funds to local government that will end councils’ need to resort to property investment. Nor have politicians yet faced up to the potential consequences of those decisions. It is unclear whether voters have any idea that their councils are engaging in potentially risky investing; should such investing force authorities into crisis, those voters may be surprised, and unhappy.

Before such a thing can come to pass, we need a comprehensive review that would ask why councils have been pushed to engage in this sort of financial engineering, and explore how to create a more sustainable and accountable system of local government expenditure.

[1] https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2018/11/23/1542975908000/The-local-government-gamble-on-commercial-property/

[2] https://www.spelthorne.gov.uk/media/20553/Draft-Statement-of-Accounts-2018-19/pdf/Draft_Statement_of_Accounts_2018-192.pdf?m=636951746361170000

[3] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/live-tables-on-local-government-finance

[4] https://www.nao.org.uk/work-in-progress/local-authority-commercial-investment/

[5] https://www.business-live.co.uk/professional-services/banking-finance/local-authorities-hit-higher-borrowing-17091832