Nicky Fairbairn, a Real Estate Partner and member of the Further Education team at International law firm DAC Beachcroft, asks Scott Corfe, Research Director at the Social Market Foundation, about the role civically minded universities will play in shaping the future of our town and city centres.

The evidence is clear that the overall impact of a university education for students is positive. For most, attending university represents a substantial return on investment, leading to an increase in lifetime earnings of over £100,000 on average even after taxes, student loan repayments, and foregone earnings while studying are taken into account. Four in every five students gain financially from attending university, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

But beyond the gains for the overwhelming majority of students, our higher education institutions have a significant role in supporting local economies and driving urban regeneration.

Universities are often among the largest local employers in their area, with 19 of them directly employing more than 5,000 people. In some places, higher education institutions are truly major local employers. There are 10 universities that account for at least 1 in every 20 jobs in the local authority areas in which they are based.

Further, higher education institutions support employment elsewhere in local communities. This includes through jobs created along their extensive supply chains ( “indirect” economic effects). The spending of university staff also generates jobs within communities (so-called “induced” economic effects), as does the spending of students.

Research by Frontier Economics has estimated that universities in England contribute about £95bn to the economy, supporting more than 815,000 jobs. A separate study by Hatch Regeneris has estimated that universities typically support up to one additional job in the immediate local economy for every person they employ directly.

These data are sometimes overlooked in political debate around HE. That’s curious, given the way some politicians are so keen to focus on place and local economic experience. Universities are big players in local economies and support a large number of well-paid jobs in parts of the country where such work is often lacking.

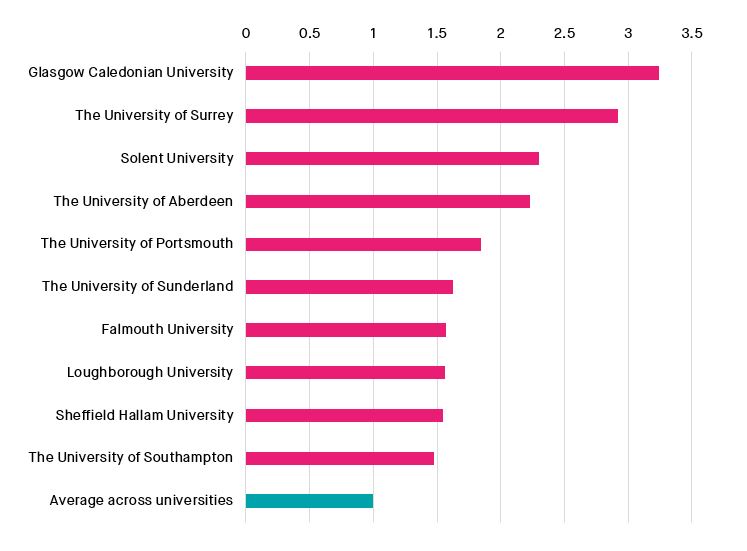

Figure 1: Number of additional jobs created in the immediate local economy, per university job

Source: SMF calculations based on Regeneris data

The SMF has long argued for better support for further and technical education, but not at the cost of HE. As Lord (David) Willetts has argued, politicians must avoid falling into the trap of thinking there is a battle between universities and other types of education provision such as local colleges, stoking a narrative that reducing university attendance or reducing funding would benefit those that do not go to university. More graduates in an area boosts the earnings of non-graduates, to the benefit of local economies, meaning that this is unlikely to be the case.

Beyond jobs and the hard economics of GDP, universities are also central to supporting urban regeneration through their cultural impact – for example with the provision of museums, art galleries, gardens and concert halls that are open to the wider public. Universities are also taking multiple steps to increase their social impact, such as through charitable activities and mentoring of local school pupils. The University of Birmingham was the first higher education institution to open a secondary school – the University of Birmingham School.

Universities should be proud of such wide-ranging impacts, but there is scope to go further. As the UPP Foundation – a charity that offers grants to universities, charities and other higher education bodies – notes, while many universities have an impressive range of civic engagement activities, few can claim to be strategically civic institutions. Further, the pressure to grow student numbers and compete on the International stage means that some universities have seen a weakening in their connection to the local community in which they operate – raising potentially uncomfortable questions about the extent to which people living in a place are benefitting from the university success story.

The 2018 UPP Foundation Civic University Commission challenged universities to re-shape their role and responsibility to their communities and to more fully realise their potential to be well-embedded in and enhancing the places in which they are based. With the aim of furthering this agenda, the Civic University Network was established in 2020, with leadership provided by Sheffield Hallam University.

A key recommendation of the UPP Commission was that universities should embark on creating Civic University Agreements – a civic strategy, informed by an analysis of local needs and opportunities, and co-created with local partners. So far nearly 60 higher education leaders have committed to preparing such agreements.

In the Social Market Foundation’s view, the COVID-19 pandemic further strengthens the need for universities to be civically-minded, playing a key role in supporting local communities. As we have previously argued, towns and cities face huge challenges going forward, with the rise of remote working and online shopping requiring a dramatic rethink of land use in urban areas as office and retail space is vacated. There is scope for higher education institutions, in partnership with local authorities, to fill this void, with an expanded educational and cultural offer in our towns and cities. We also see scope for more and better co-operation between universities and FE providers in their local communities.

As the same time, universities face risk of further backlash as we emerge from the pandemic, especially if they pursue a strategy that sees them becoming increasingly distant from their local community – for example, with a shift to much higher rates of online rather than in-person teaching which sees a growing detachment between a university’s base and the geographical placement of its students. Online learning brings with it benefits, including an ability for universities to expand their reach and impact, including through free Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). But there are also fears that it will just be used as a “cost-cutting exercise, brought about by universities needing to stay financially afloat in a marketised system”, something which sees a significant weakening in the local-level civic role of universities.

The 2020s should be a period in which universities become increasingly engaged with the businesses and people that surround them – a decade in which civically-minded institutions play a leading role in shaping the future of town and city centres, enriching local culture, and providing the upskilling of the population needed to keep Britain’s economy competitive.

Getting there is going to require more support and a change of tone from Government, especially given the false narrative that universities only benefit graduates or even worse just a small proportion of them. This is far from the truth.