Five years ago, Liz Truss spoke at an SMF event on the benefits of competition in a market economy. Scott Corfe looks at how much has changed since then, arguing that "Trussonomics" must focus on making consumer markets more competitive - both to accelerate economic growth and tackle the cost of living crisis.

Competition is an area we need to be constantly vigilant about… we need to be absolutely careful to say that the benefits of competition are huge and the benefits of the way we operate a market economy are huge.

~ Liz Truss, then Chief Secretary to the Treasury, at an SMF event at the 2017 Conservative Party conference.

It was the launch event for a report, authored by myself and Nicole Gicheva, which explored the extent to which markets in the UK matched the economic ideal of “perfect competition” – where firms vie intensely for customers and there is continuous downward pressure on prices and upward pressure on quality.

This notion of competition is often used to extol the prevailing relatively “free market” British economic model. Yet, as our analysis showed, many of the markets that consumers interact with on a daily basis fall far short of the perfect competition ideal. From banking to telecoms to energy, a small number of firms dominate the market.

This would not be a problem in itself, if it meant that these titans are competing intensely to attract customers and their size is translating into efficiency gains and lower prices.

However, the reality is that consumer inertia is often pervasive, driven by a complex range of factors from vulnerability (e.g. financial distress and mental health issues) to customers being baffled by the complexities involved in navigating often complicated markets. With only a small share of customers switching banks, broadband provider, or gas and electricity supplier each year, large companies in these sectors face scant pressure to up their game.

Have things changed much since Liz Truss spoke to us in 2017? The picture is complicated.

First, the positive – Banks are under increasing competitive pressure, due to new entrants

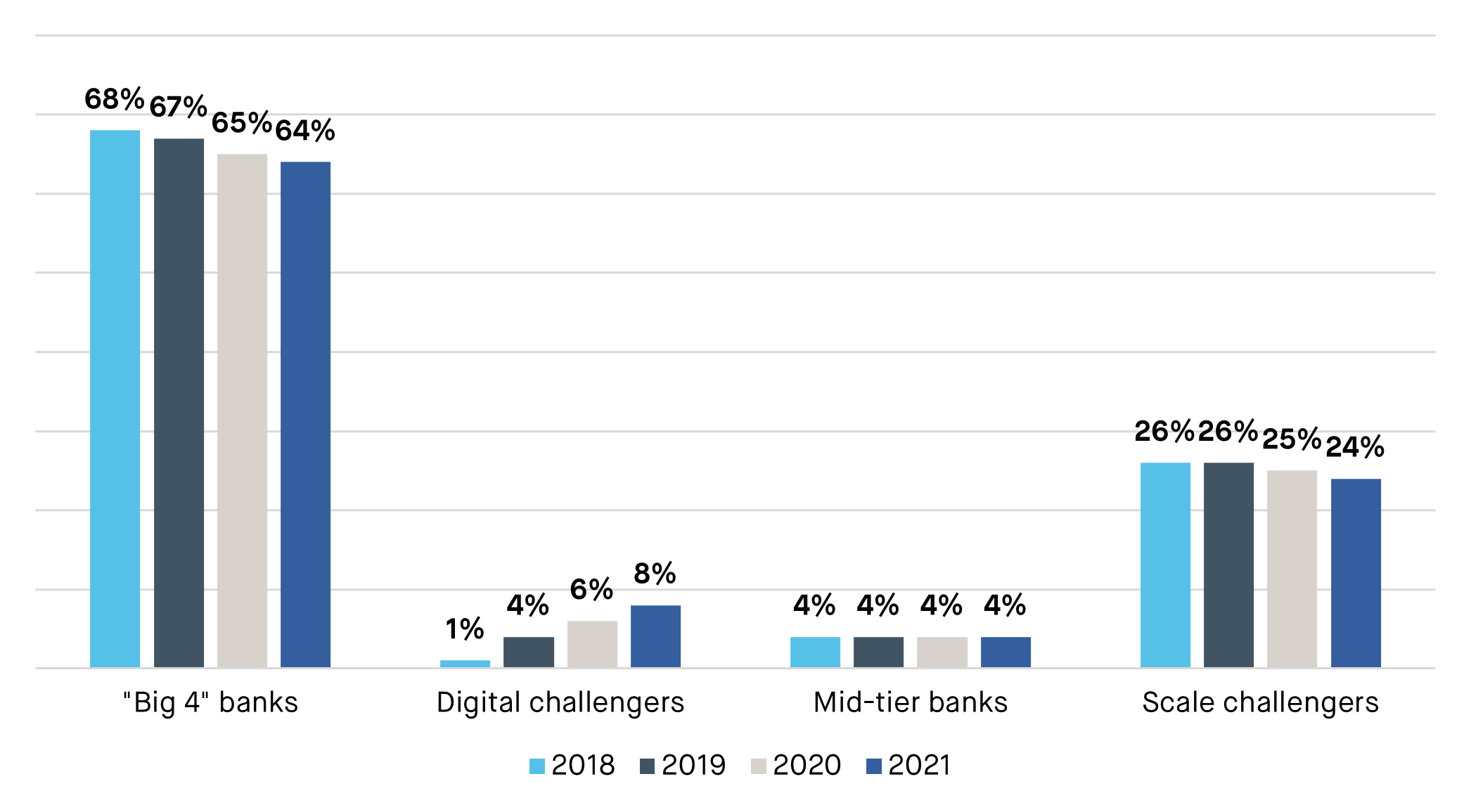

Financial services may be turning a corner. Britain’s largest banks are becoming subject to increasing competition as more consumers embrace smaller “challenger” banks, including digital-only ones. According to Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) analysis, the market share of digital challenger banks in the Personal Current Account (PCA) market increased rapidly from 1% in 2018 to 8% in 2021. As the FCA’s 2022 Strategic Review of Retail Banking Business Models noted, the increasingly competitive banking environment appears to be improving customers’ outcomes, including in the form of better mortgage deals. The FCA also noted that service quality has improved as larger banks have adopted digital innovation – such as app-based budgeting tools – led by the digital challengers.

Figure 1: Share of personal current accounts by account numbers

Source: FCA analysis

Less positive – Consumer harm in telecoms market is being overlooked

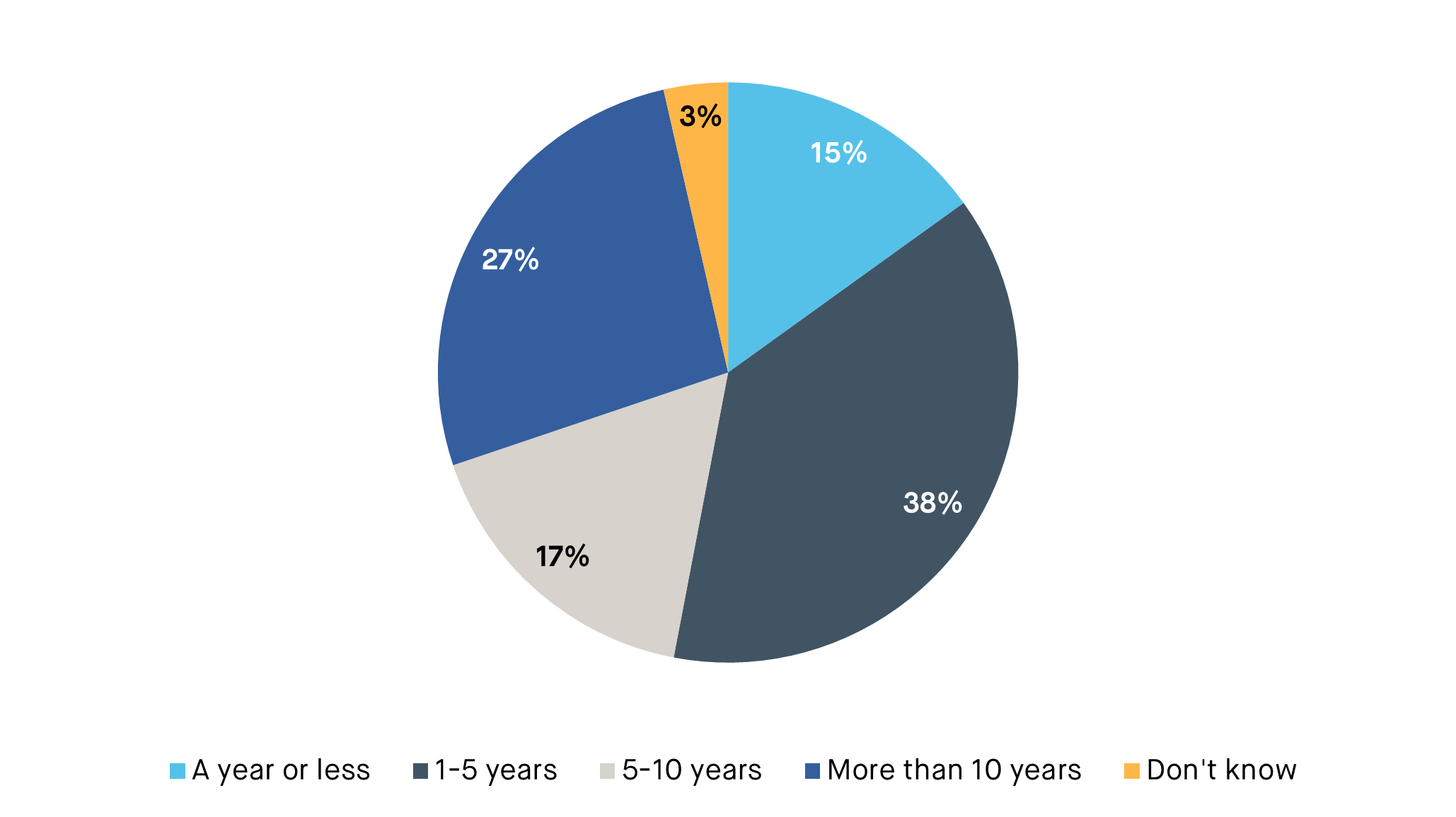

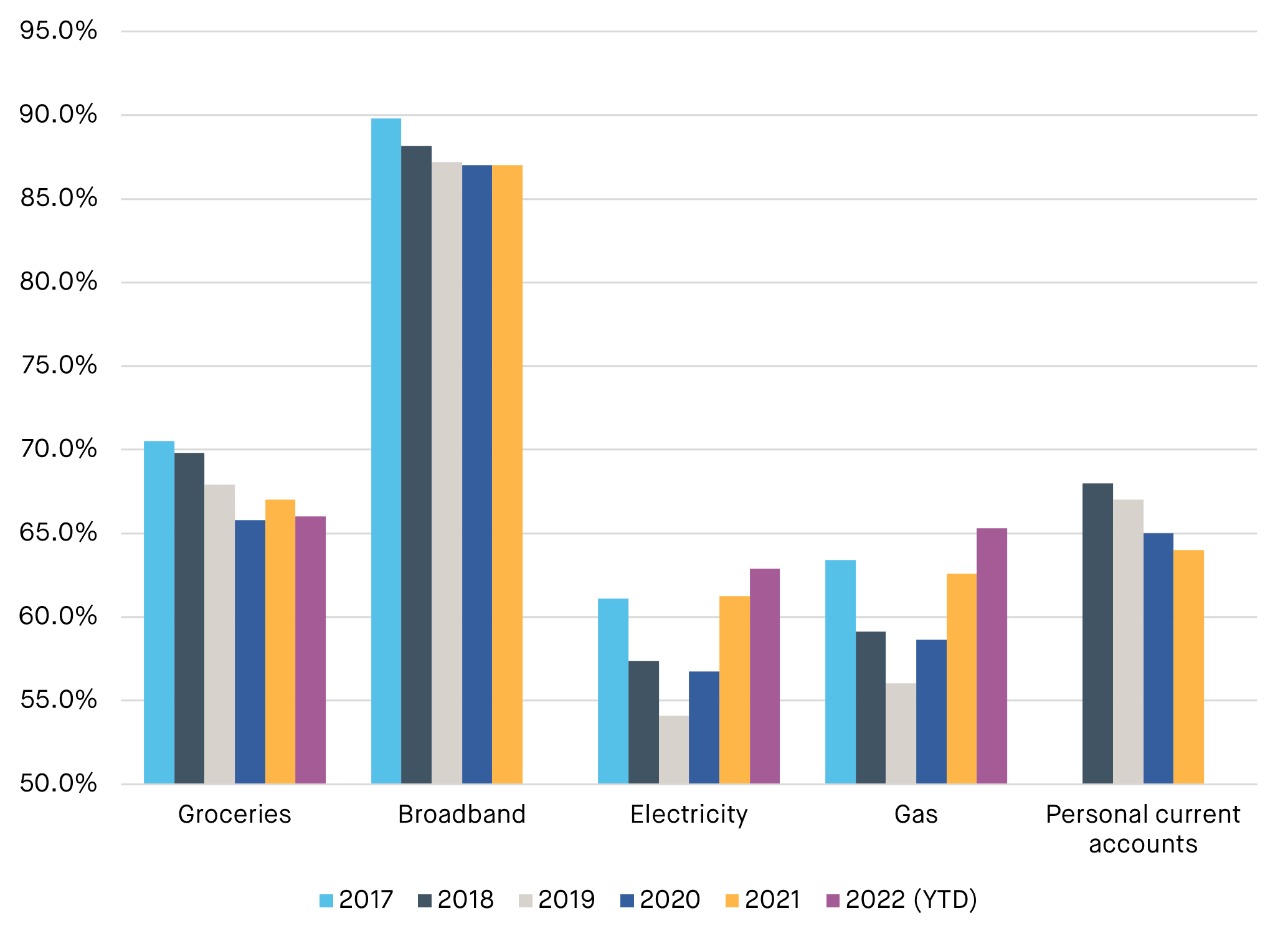

The telecoms market remains a major concern to us, as it did in 2017, with consumer detriment here continuing to be overlooked in political and policy debates. Our analysis suggests that, as of 2021, the four largest broadband internet service providers have a market share of 87%, only marginally lower than the 90% seen in 2017. Ofcom’s 2021 Switching Tracker shows that a quarter (27%) of households have been with the same broadband provider for over 10 years, with a further 17% between 5 and 10 years. Just 15% of households said they had been with their broadband provider for less than a year.

This matters because, according to analysis published by Citizens Advice this year, seven million broadband customers face a loyalty penalty of £61 per year as a result of staying in their contracts after the initial contract period ends, meaning an aggregate cost to households of over £400 million. Other areas of detriment include customers receiving slower-than-advertised broadband speeds and simply being on poor value products. With the rise of bundling in the telecommunications space – with consumers opting to receive mobile telephony, broadband and sometimes pay TV from the same supplier – it can be difficult to unpick the value for money of different offers.

Figure 2: Length of time with broadband provider

Source: Ofcom Switching Tracker 2021

And energy: An area where we were overoptimistic on emerging competition

The SMF previously highlighted the energy market as an area where increasing competition was leading to a significant improvement in consumer outcomes, with companies outside the “Big 6” offering cheaper electricity and gas deals to customers.

Yet this state of affairs rested on rocky foundations, with too many smaller suppliers having financially unsound business models that insufficiently hedged against surging wholesale energy prices. 28 energy firms collapsed in 2021, displacing over four million customers. 2022 has seen customer switching between suppliers collapse as fixed rate tariffs have soared. After years of reduced concentration in the hands of the largest suppliers, the energy sector is consolidating, raising questions around how the market will function once we exit the current period of extraordinarily higher gas and electricity prices.

Figure 3: Market share of largest four firms in consumer market, in terms of number of customers

Source: SMF analysis

Consumer markets and Trussonomics

Liz Truss and her Chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, appear keen to demonstrate a clean break on economic policy, with much emphasis on being willing to do whatever it takes to unlock growth. They are also under enormous pressure to tackle the rising cost of living, which is currently far outstripping growth in people’s pay packets.

A focus on making consumer markets function better must play a role in both of these areas. Eradicating the £1.3 billion a year in “loyalty penalties” in the broadband, mobile and mortgage markets, for example, would be a welcome boost to household finances.

Placing more pressure on businesses to compete with each other would also make firms more productive, encouraging them to make investments that improve service quality and reduce prices. IMF research has previously found that excess profits – arising from a lack of competition – drive down business investment and innovation rates in the long run. Conversely, tackling excess profits through competition-enhancing measures would drive up business investment and in turn economic growth.

What does this mean in terms of the policy platform of the new Government? Many of the SMF’s previous recommendations in this space remain relevant. A “presumption in favour of competition” at the heart of merger & acquisition policy would be welcome, as would the creation of a Minister for Competition and Consumers to ensure that competition issues are prioritised across government.

Policy also needs to tackle the “barriers to scale” that can make it hard for challenger firms to expand beyond a certain point – such as regulatory costs and difficulty accessing the finance needed to grow. While it is encouraging to see the digital challenger banks gaining market share, they may be hitting limits to their growth; the FCA’s Strategic Review of Retail Banking found that, relative to the major banks, a smaller proportion of the digital challengers’ Personal Current Accounts are main accounts. This results in lower balances, lower volumes of transactions, and lower overdraft usage, leading to lower funding benefits and less scope to generate fee income. The SMF has previously argued that the Financial Service Compensation Scheme (FSCS) should provide enhanced rates of deposit protection for challenger banks, to encourage more people to use these banks for their main current account.

There is also huge potential for government to support the harnessing of technology to make Britain’s markets “hyper competitive” – for example, through the creation of next generation automated switching services that ensure consumers are accessing the best offers on the market. Open banking could unlock such possibilities in the financial services space.

Elsewhere in the field of competition, there is unhelpful uncertainty about the Competition and Markets Authority’s (CMA’s) Digital Markets Unit (DMU). This was set up with the promise of giving Britain’s authorities the tools to drive up competition in online markets that are often dominated by a small number of giant providers. But more than a year on, the DMU still lacks statutory powers. The Truss Government’s willingness to give it the powers it needs could serve as a litmus test of the new administration’s views on competition. Is the new government team really serious about seizing the opportunity to make Britain a world-leader in competitive markets, with all the benefits that could bring for consumers and growth?

Britain should aspire to have some of the most competitive, dynamic consumer markets in the world. To get there, the Truss Government needs to acknowledge that such markets often fail to occur naturally. In sectors like finance, tech, energy and telecoms they need taming, with a regulatory and policy regime that curbs market power, supports new entrants and acknowledges consumer inertia. A failure to recognise this – and instead seeing “pro-market” policy through the narrow lens of tax cuts – would be detrimental to a go-for-growth agenda. It will also leave households short-changed.