The Government’s efforts to designate this past week “crime week”, with the announcement of a new drugs strategy had the effect of – briefly – drawing attention to its record on criminal justice. According to the New Statesman’s Stephen Bush “cuts to the criminal justice system and front-line policing mean that, as it stands, a large number of criminal offences in the United Kingdom have been de facto decriminalised. Unless you are speeding or planning on a little light murder, your chances of being caught are pretty slim”. In fact, official crime stats suggest that things are a little more complicated than that.

The chart below shows that the number of offences reported to the police (and it is worth emphasising that only around two-fifths of crimes are reported) that result in a charge or summons has indeed halved. Back in 2015, 16% of recorded crimes ended up in court; in the year to March 2021, it was 7%. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean crimes are going undetected: the proportion of investigations that were closed with no suspect is also down, from 49% six years ago to 36% this year. So what is going on?

Figure 1: Share of Recorded Crime Outcomes in England and Wales, Year to March

Source: Home Office, Crime Outcomes in England and Wales 2020 to 2021

The last six years have seen a dramatic increase in the number of cases that are ended because of ‘evidential difficulties’. In particular, the proportion of recorded crimes where the victim does not support further action has risen from 9% in 2015 to 26% in 2021.

Figure 2: Share of Recorded Crimes in England and Wales where victim does not support further action, Year to March

Source: Home Office, Crime Outcomes in England and Wales 2020 to 2021

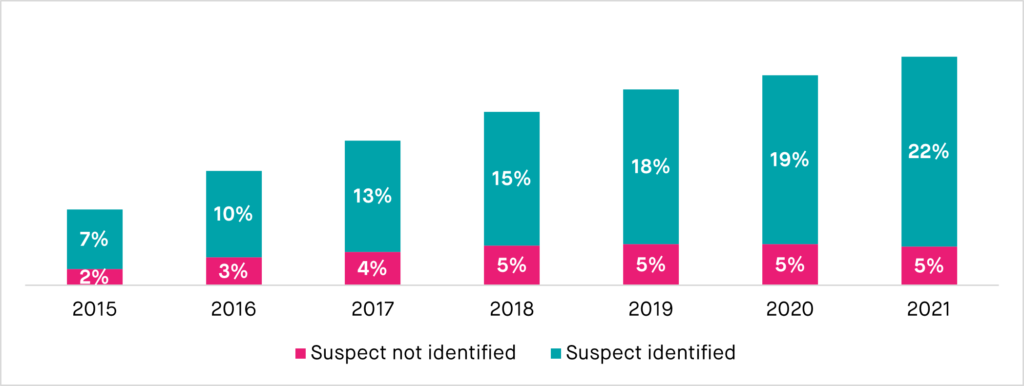

It’s possible to attribute this to a lack of police resources – perhaps some victims are waiting so long for their cases to be resolved that they are giving up. But the striking thing is that in around of 80% of cases where victims drop out, the police record there being a suspect.

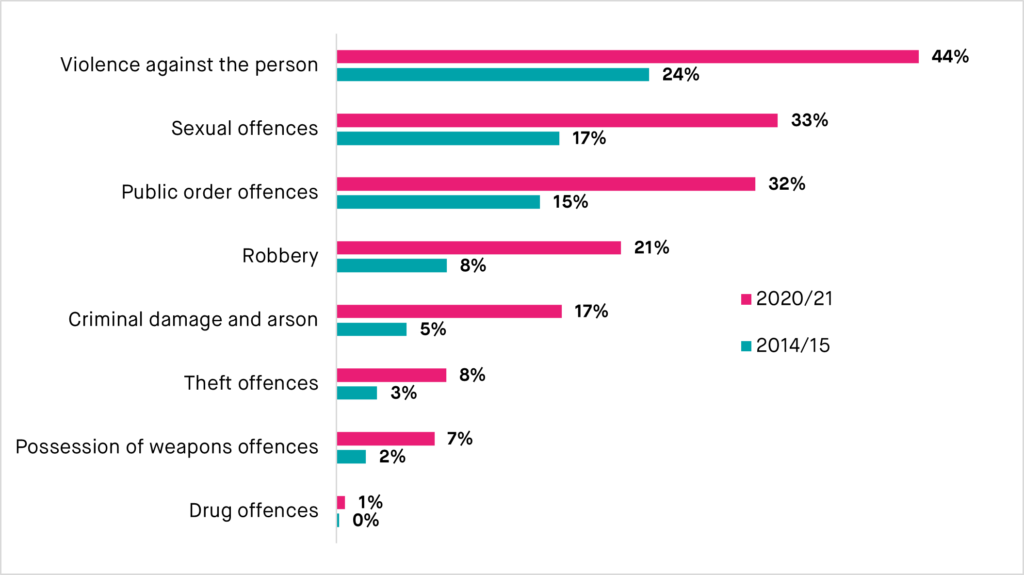

There are a number of theories to explain this phenomenon of rising “victim attrition”. A 2019 Home Office report links it to improvements in crime recording and a change in the mix of crimes that police deal with towards a higher share of sexual offences and domestic abuse that can be harder to resolve.

Yet the chart below shows that the issue extends to other types of crimes such as robbery, criminal damage, and theft. A report earlier this year from the Criminal Justice Chief Inspectors attributed it to delays in delivering justice, both in terms of prosecuting and hearing cases – especially in the wake of the pandemic. But the average case of victim attrition is recorded after just 14 days – and that number has gone slightly down since 2016.

Figure 3: Share of Recorded Crimes in England and Wales where victim does not support further action, by offence type

Source: Home Office, Crime Outcomes in England and Wales 2020 to 2021; Crime Outcomes in England and Wales 2014 to 2015.

The truth is that we don’t know for sure what is going on. As the Victims’ Commissioner Dame Vera Baird said in May: “This raises a lot of questions… Is there a sense of no action from the police? Is there a sense that the CPS won’t charge? We don’t have the granularity of data to be sure. But it’s clear that this trajectory is no good for anyone and this cannot carry on – we must get to the bottom of this.” She’s right.