Childcare costs in the UK are contributing to poverty and gender inequality. As part of our cross-party Commission on Childcare, we're publishing new analysis on the extent of the childcare crisis - the impact of being dragged out of the labour market to look after children has a long-term, scarring effect on wages. We'll be engaging with stakeholders and developing policy solutions later in the year.

Childcare costs are contributing to poverty. Government needs to act.

The SMF recently launched a cross-party Commission on Childcare, supported by John Penrose MP and Siobhain McDonagh MP. Through engagement with expert stakeholders, and new research, we want to provide policy solutions to reduce childcare costs in the UK, which are among the most expensive in the world.

Impact of childcare costs on those on low incomes

The Commission is particularly concerned about the impact of childcare costs on those on lower incomes.

- New SMF analysis found that childcare accounts for 7% of household income among those paying for it, rising to 17% for those in the bottom income quintile.

- A third of childcare users in the bottom income quintile are in childcare poverty, defined as costing more than 20% of household income.

- For many, costs are simply too prohibitive. Three-quarters (76%) of households with an income above £45,000 use formal childcare, compared with only half (52%) of those with an income below £10,000.

The motherhood penalty on women’s earnings

Those opting out of childcare because of the expense face other costs – in particular, reduced income from being unable to work as many hours. Women are particularly affected by this.

- For about a third of mothers out of work with young children, childcare costs are the leading reason for not working.

- Half of part-time working mothers that want to work more, say that affordable childcare would help

Long-term scarring of wages

These are not just temporary costs faced by families and, especially, women. The impact of being dragged out of the labour market to look after children has a long-term, scarring effect on wages. This analysis is displayed in the charts below.

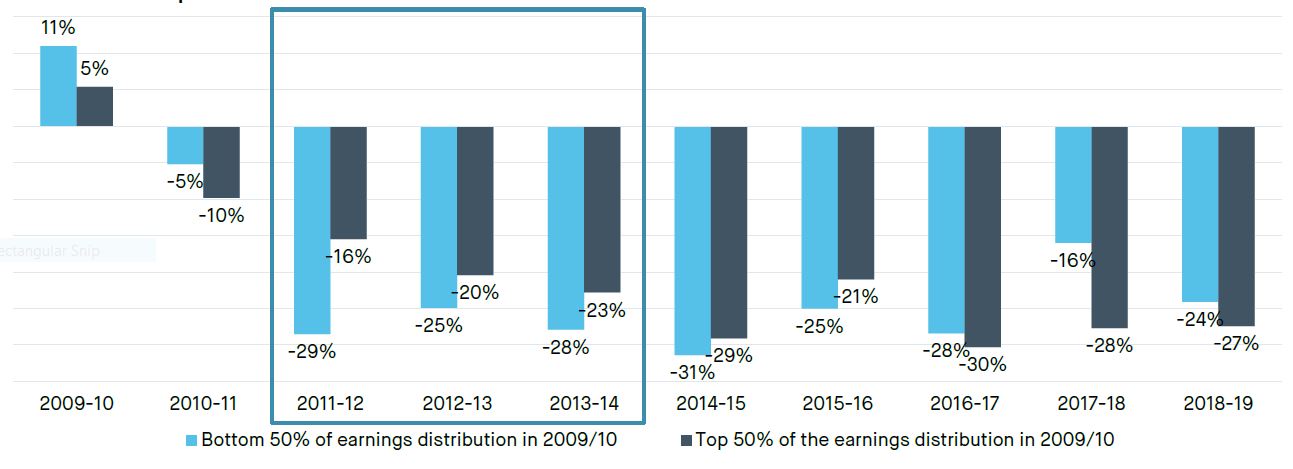

Figure 1: % difference in female wages – those that had first child in 2010/11 or 2011/12, versus those that had no children over entire time period

Source: SMF analysis of Understanding Society. Analysis of women aged 25-35 in 2009/10

We find that, even by 2018/19, women that had children faced a “motherhood earnings penalty” of about a quarter. This shortfall is similar among those in the bottom and top half of the income distribution.

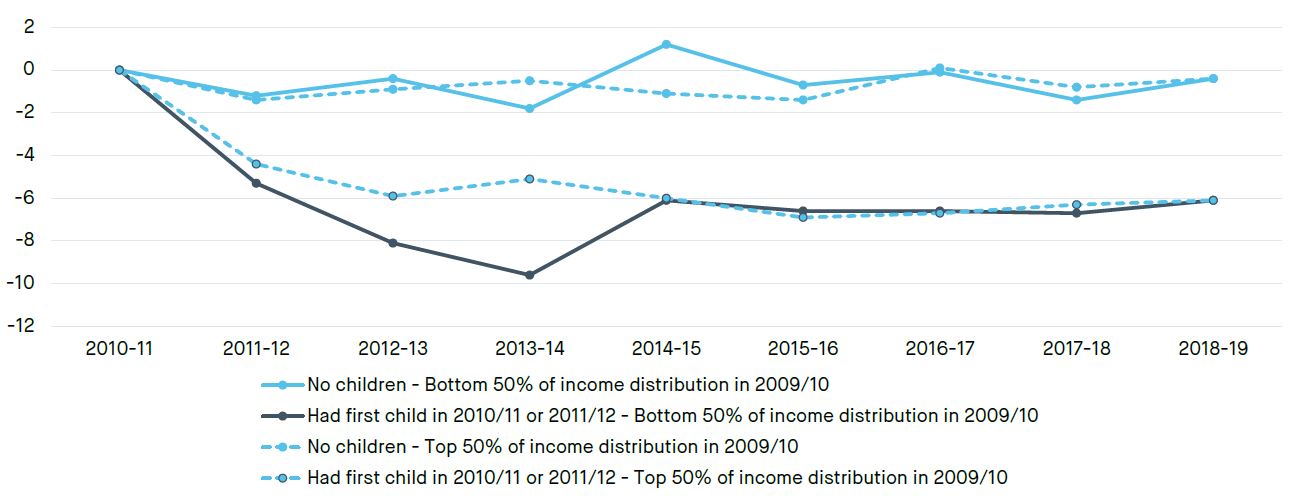

We find that women in the bottom half of the income distribution face a greater income hit in the early years of parenthood, in percentage terms, with a key driver of this being a much sharper decline in hours worked (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Change in mean hours worked among women aged 25-35 in 2009/10, by whether had children

Source: SMF analysis of Understanding Society. Analysis of women aged 25-35 in 2009/10

Something needs to be done to reduce the impact of childcare costs on household budgets and the ability of women to remain – and flourish – in work. With the UK in the grip of a cost-of-living crisis, politicians looking to provide solutions need to ensure that fixing childcare is a high priority.

If you’re interested in the issue, please read our read our call for evidence, and reach out to us at richa@smf.co.uk.